Effects of 10-min prewarming on core body temperature during gynecologic laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial

Article information

Abstract

Background

Previous research has shown a beneficial effect of prewarming for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. However, there are few studies of the effects of a short prewarming period, especially in gynecologic laparoscopic surgery.

Methods

Fifty-four patients were randomly assigned to 2 groups. Patients in the non-prewarming group were only warmed intraoperatively with a forced air warming device, while those in the prewarming group were warmed for 10 min before anesthetic induction and during the surgery. The primary outcome was incidence of intraoperative hypothermia.

Results

Intraoperative hypothermia was observed in 73.1% of the patients in the non-prewarming group and 24% of the patients in the prewarming group (P < 0.001). There were significant differences in core temperature changes between the groups (P < 0.001). Postoperative shivering occurred in 8 of the 26 (30.8%) patients in the non-prewarming group and in 1 of the 25 (4.0%) patients in the prewarming group (P = 0.024).

Conclusions

Forced air warming for 10 min before induction on the operating table combined with intraoperative warming was an effective method to prevent hypothermia in patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopic surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia (IPH) is defined as a core body temperature below 36.0°C [1]. Perioperative hypothermia is associated with higher incidence of ischemic heart disease [2], surgical wound infection, and prolonged hospitalization [3]. In addition, it increases blood loss [4] and delays postanesthetic recovery [5].

A forced air warming system is currently the most widely used perioperative warming method [6]. However, several previous studies show that conventional intraoperative warming with a forced air warming device is not enough to avoid IPH [7,8]. This suggests that additional methods are needed to prevent IPH.

The main cause of the rapid drop in body temperature during the first hour after the initiation of anesthesia is core-to-peripheral thermal redistribution [9]. In addition, the amount of heat lost and the rate of the core body temperature drop depend on the temperature gradient between the central and peripheral compartments. Prewarming, that is warming the surface of the body before the induction of anesthesia, can reduce the temperature difference between the core and periphery. Thereby, it decreases the degree of core-to-peripheral thermal redistribution [10]. The national institute for health and clinical excellence guidelines recommend 30 min of prewarming to minimize the incidence of IPH [1]. However, adopting this idea as a daily clinical practice remains a hardship because 30 min is a significant amount of time in a fully scheduled operating environment. Therefore, the need for research to investigate the effectiveness of a short period of prewarming has emerged. Although a few studies show that 10 min of prewarming reduces the risk of IPH [11,12], a sufficient amount of research has not been performed yet. Furthermore, there has been no research on the effects of a combination of 10 min prewarming in the operating table and intraoperative active warming during gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. This study was designed to test whether IPH could be prevented by performing 10 min of prewarming combined with conventional intraoperative active warming with a forced air warming system in patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopic surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital (no. CR-18-174) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (no. NCT04027842). We enrolled patients between the ages of 19 and 75 years with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status 1 or 2 who underwent gynecologic laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. Criteria for exclusion from this study were preexisting hypothermia (< 36℃) or hyperthermia (> 37.5℃), anesthesia lasting for < 1 h or > 2 h, and conversion from laparoscopic surgery to laparotomy. We also excluded patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 31 kg/m2 and known thyroid disease. With written informed consent, eligible patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups using a computerized random number generator (http://www.randomization.com). An assistant put the patient’s allocation into a sealed opaque envelope, which was opened immediately after the patient entering the operating theater.

Prewarming was done on the operating table before anesthesia induction. Core body temperature was measured using an infrared tympanic thermometer (ThermoScan-IRT6520, Braun GmbH, Germany) when the patients were not intubated. After intubation, an esophageal thermometer (ST probe EST16, S&S Med, Korea) was used for measuring core body temperature. The core body temperature of all the patients was measured using an infrared tympanic thermometer as soon as the patient arrived at the operating theater.

In the non-prewarming group, induction was done immediately after measuring the core body temperature using an infrared tympanic thermometer. In the prewarming group, patients were warmed preoperatively with a forced air warming device (WarmTouch WT 6000 Warming Unit, Medtronic, USA) for 10 min in the operating theater. After 10 min of prewarming, the tympanic body temperature was measured, and anesthesia was induced promptly. In both groups, forced air warming was performed over the entire body with a cotton blanket from the time of anesthesia induction.

Total intravenous anesthesia was administered using propofol and remifentanil with a target effect-site concentration controlled infusion (Orchestra Base Primea, Fresenius Vial, France), which was set by the Schneider model for propofol and the Minto model for remifentanil. To induce anesthesia, the effect site concentration was targeted with 4 μg/ml of propofol and 4 ng/ml for remifentanil. Rocuronium (0.8 mg/kg) was administered as neuromuscular blocking agent at the induction. Patients were intubated when train-of-four (TOF) count became 0 and Bispectral index (BIS) below 60. TOF count was measured every 5 min and BIS was monitored throughout the procedure.

After intubation, we inserted an esophageal thermometer and the patients’ temperatures were recorded at 15 min intervals until the end of the surgery using the esophageal thermometer. Also, the warming areas were switched from the whole body to the upper trunk and extremities to allow access to the surgical field. Active warming was continued until the patients left the operating theater, unless the core body temperature was > 37℃, due to concern for patient safety.

The ambient temperature of the operating theater was maintained between 21–22℃ by the hospital central control system. The warming device for intravenous and irrigation fluid was not used, and all the administered fluids were kept at room temperature.

After the patients were transferred to the post-anesthetic care unit (PACU), core body temperature was measured by a tympanic membrane thermometer and postoperative shivering was graded by an researcher who was blinded to the procedure in the operating room. Shivering was divided into four grades (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe: The Bedside Shivering Assessment Scale) [13].

The primary outcome was the incidence of intraoperative hypothermia, defined by core body temperature < 36℃. We recorded the body temperature at each time point and counted the number of patients whose core temperature was < 36℃ while under anesthesia. The secondary aim was time-prewarming interaction for the initial hour of anesthesia to analyze the effect on redistribution hypothermia. In addition to body temperature and shivering grade, demographic and baseline characteristics were recorded. We also recorded ambient temperature, estimated blood loss, input of intravenous fluid, and the amount of irrigation fluid.

The number of patients required for this study was based on a preliminary study. In the preliminary study, 28 patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopic surgery were randomly allocated at a ratio of 1:1 to either the non-prewarming or 10 min-prewarming groups. Ten of the 14 patients in the non-prewarming group and 2 in the prewarming group suffered intraoperative hypothermia. Based on this result, we calculated the sample size to achieve 80% statistical power with an alpha error rate of 0.05 (two-tailed) and 24 patients per group were required. Considering a 10% dropout rate, the total sample size was 27 patients for each group.

All data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics for Windows version 25 (IBM corp., USA). Normally distributed continuous data are shown as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the student's t-test. Continuous variables that were not normally distributed are described as median (1Q, 3Q) and were compared via the Mann–Whitney U test. Comparison of categorized variables are presented as number of patients (%) and analyzed with the chi-squared test. To determine the time-prewarming interaction, a repeated-measures ANOVA was performed with ‘time’ as the repeated measure and ‘prewarming’ as a factor, followed by the Bonferroni correction.

RESULTS

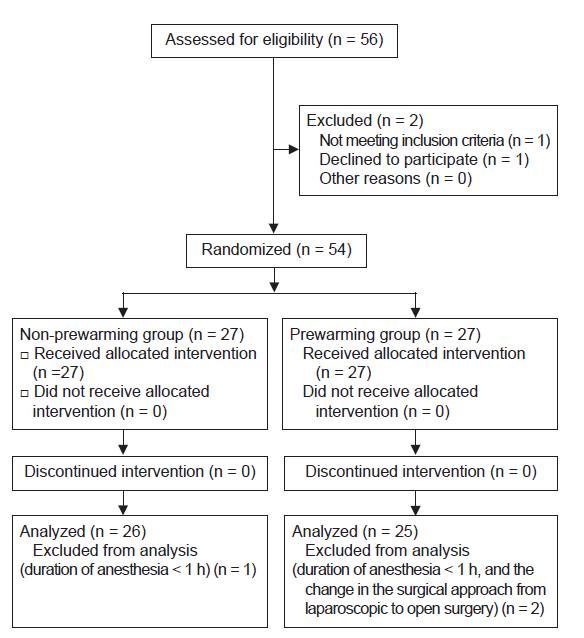

Of the 54 participants, 2 were excluded because the duration of anesthesia was < 1 h. In addition, one patient’s procedure was changed to a laparotomy during the surgery and was excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1).

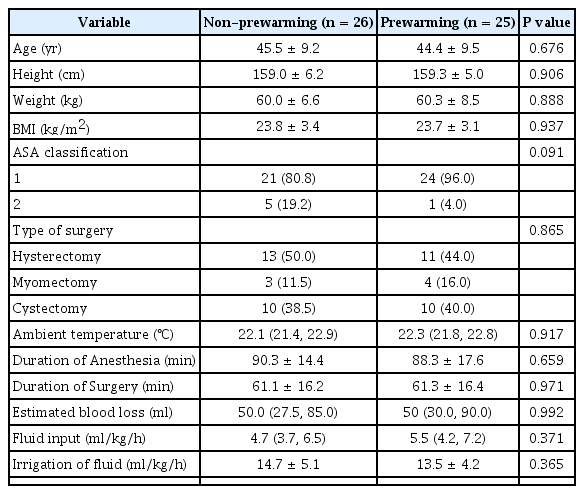

Age, height, weight, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status, type of surgery, ambient temperature, duration of anesthesia, operating time, blood loss, amount of administered fluid, and irrigation fluid were similar in the two groups (Table 1).

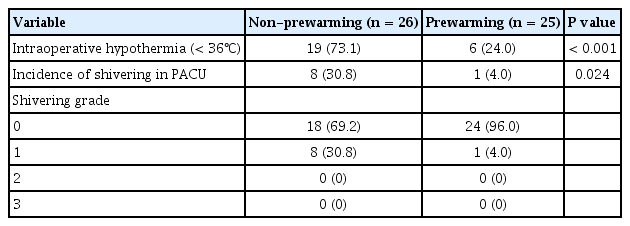

The incidence of intraoperative hypothermia was higher in the non-prewarming group (73.1%) than in the prewarming group (24%) (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Core body temperature on arrival in the operating theater (P = 0.168) and before induction (P = 0.614) did not differ significantly between the two groups and the 10 min prewarming did not significantly increase core body temperature (P = 0.534). However, the core body temperature of the non-prewarming group was lower at the end of the surgery (P < 0.001). There were significant differences in core temperature changes between the non-prewarming and prewarming groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Postoperative shivering occurred less in the prewarming group in the PACU (Table 2; 30.8% vs. 4.0%; P = 0.024).

Mean core body temperature during the perioperative period in the non-prewarming (♦) and prewarming groups (■). Temperatures at the arrival in the operating theater, before induction, and at the arrival in the post-anesthetic care unit (PACU) are tympanic membrane temperatures; temperatures at other time points are esophageal temperatures. Half error bars represent the SD (*P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Prewarming for 10 min before induction on the operating table combined with the intraoperative warming was an effective method to prevent hypothermia in patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopic surgery.

In gynecologic laparoscopic surgery, IPH is a common problem. The minimally invasive procedure was predicted to reduce intraoperative heat loss compared with open surgery which exposes the viscera. However, there were no significant differences in intraoperative body temperatures between laparoscopic and open surgeries [14,15]. This is because laparoscopic surgery, unlike open surgery, requires carbon dioxide (CO2) gas for abdominal inflation. CO2 gas is conventionally used at a temperature of 21℃ with no extra warming [16]. There was also a report that women had a higher incidence of hypothermia than men [17]. In addition to this, because gynecologic laparoscopic surgery necessitates the lithotomy position, very limited body surface area, including part of the upper trunk and both upper extremities, can be warmed with the forced air warming system.

Previous studies showed that intraoperative active warming alone is not enough to maintain normothermia and emphasized the importance of prewarming [18,19]. Accordingly, our study results correspond well with those findings. Intraoperative warming with a forced air warming system did not effectively prevent intraoperative hypothermia in patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Ideally, 30 min of prewarming and a combination of various methods such as warming intravenous fluid and humidifying respiratory gases with intraoperative forced air warming are most helpful to maintain normothermia during surgery [11,18]. However, it is not always possible to apply all these methods in clinical practice. A forced air warming system is now commonly used in most centers and 10 min was an acceptable amount of prewarming time [12]. This is reason why we chose 10 min-prewarming as an additional way to prevent IPH.

To keep the final core temperature in the normal range, we consider 10 min prewarming beneficial, especially for patients undergoing surgery for about 1 hour according to the present results. During long operations, patients tend to be normothermic at the end of surgery because core temperatures start to rise after thermal redistribution is completed if patients are kept well warmed [19]. However, in shorter procedures, especially those for about 1 h, it is more difficult to avoid hypothermia at the end of surgery compared to longer operations [19].

One of the differences compared to previous short-term prewarming studies is the location where prewarming was performed [20,21]. In this study, patients were warmed preoperatively in the operating table and that may have had beneficial influence on the results. Although further studies are needed to compare the actual amount of heat among patients prewarmed in other locations, it is likely that the prewarming location affects the quality of warming, particularly in prewarming for a short period. If patients are warmed preoperatively in an environment other than the operating table, active warming cannot be maintained during the transfer to the operating theater. This results in patients losing part of the thermal energy obtained by the short period of prewarming. In contrast, if the prewarming is done in the operating table, the gap between prewarming and induction disappears, which enables less net heat loss.

There are limitations in the interpretation of our results. We used an infrared tympanic thermometer to measure the core body temperature before patients were intubated, and esophageal temperature was measured only after tracheal intubation. Controversy exists regarding accuracy of a tympanic thermometer on assessing core body temperature. There may be a difference between the actual core body temperature and the temperature we measured with the tympanic thermometer. However, we tried to minimize the bias by using the average of the bilateral tympanic temperatures, according to the recommendation of a previous study [22]. Another limitation is that double blinding was impossible with our study design. The researchers were blinded, but patients knew which group they belonged to. Nevertheless, since data with the patients’ subjective involvement was not collected, it is unlikely that this factor had an impact on our outcome. One more limitation is that we did not measure the peripheral temperature and heat content. Core to peripheral redistribution hypothermia depends on the temperature gradient between the core and peripheral compartments. Although we did not measure peripheral temperature, prewarming can reduce the normal core to peripheral heat gradient by raising the peripheral temperature. This can reduce the heat redistribution that occurs after inducing anesthesia.

In conclusion, among patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopic surgery, warming patients for 10 min preoperatively on the operating table is associated with better management of perioperative body temperature and can prevent intraoperative hypothermia.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: So Young Lee, Jin-Yong Jung. Data acquisition: So Young Lee, Jin-Yong Jung, Soo Jin Kim. Formal analysis: So Young Lee, Soo Jin Kim. Supervision: Jin-Yong Jung. Writing—original draft: So Young Lee. Writing—review & editing: Jin-Yong Jung, Soo Jin Kim.