Challenging issues of implementing enhanced recovery after surgery programs in South Korea

Article information

Abstract

This review discusses the challenges of implementing enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs in South Korea. ERAS is a patient-centered perioperative care approach that aims to improve postoperative recovery by minimizing surgical stress and complications. While ERAS has demonstrated significant benefits, its successful implementation faces various barriers such as a lack of manpower and policy support, poor communication and collaboration among perioperative members, resistance to shifting away from outdated practices, and patient-specific risk factors. This review emphasizes the importance of understanding these factors to tailor effective strategies for successful ERAS implementation in South Korea’s unique healthcare setting. In this review, we aim to shed light on the current status of ERAS in South Korea and identify key barriers. We hope to encourage Korean anesthesiologists to take a leading role in adopting the ERAS program as the standard for perioperative care. Ultimately, our goal is to improve the surgical outcomes of patients using this proactive approach.

INTRODUCTION

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is a comprehensive perioperative care concept that focuses on an evidence-based, multidisciplinary, standardized, and patient-centered approach [1] with the aim of minimizing perioperative stress and enhancing the quality of postoperative recovery [2]. With its proven efficacy, ERAS has demonstrated remarkable benefits, including a reduction in hospital stay duration and a decrease in postoperative complications [3-5]. Originally introduced for colorectal surgery, the application of this innovative approach has expanded to various surgical specialties, including major abdominal, head and neck, spinal, obstetric, orthopedic, breast, thoracic, and cardiac surgeries [6]. Consequently, ERAS has gradually emerged as the gold standard for perioperative care across different types of surgical interventions.

Despite the well-documented benefits of ERAS in improving postoperative recovery, effective implementation in clinical settings remains challenging. The successful implementation of ERAS in clinical practice necessitates alterations to conventional clinical workflows, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and embracing evidence-based practices. Unfortunately, various barriers impede ERAS [7]. Additionally, the cultural and organizational context of healthcare facilities significantly influences the introduction and implementation of ERAS. Consequently, understanding these factors is pivotal for tailoring strategies that can overcome barriers and foster the successful implementation of ERAS in clinical practice.

Therefore, we review the current status of ERAS implementation in South Korea and discuss the challenges surrounding its adoption. By addressing these hurdles, Korean anesthesiologists can improve patient outcomes and enhance perioperative care. The main purpose of this review was to discuss the barriers to implementing ERAS in the Korean medical environment, taking into consideration Korea’s unique healthcare setting. Such considerations will aid in devising effective strategies for the successful implementation of ERAS in South Korea.

CURRENT STATUS OF ERAS IN SOUTH KOREA

Several surveys conducted among general surgeons to examine the current status of ERAS implementation in South Korea [8-10]. In a survey of 89 gastric surgeons, 65.2% said that they were familiar with the concepts and details of ERAS, but only 33.7% applied it with all patients [8]. In another survey of 127 hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgeons, only 18.2% and 35.0% of ERAS protocol items for pancreaticoduodenectomy and hepatectomy, respectively, were followed by more than half of the respondents [9]. In a survey of general surgeons from various specialties, 68.6% of the respondents said they were aware of the concept of ERAS, but only 33.7% said they were implementing an ERAS program in their practice [10]. According to these surveys, the rate of actual ERAS implementation in clinical settings was markedly lower than the level of awareness of ERAS.

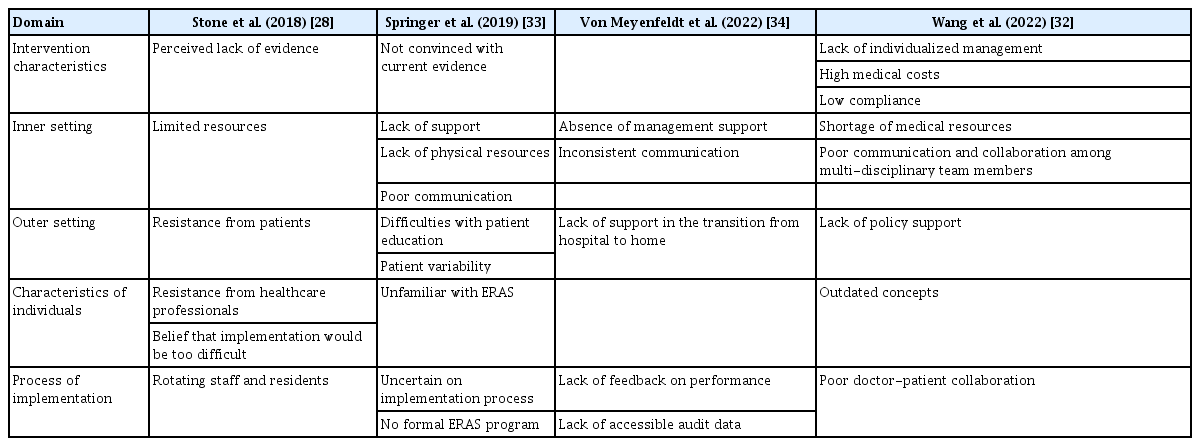

However, no study has examined the implementation status of ERAS from the perspective of anesthesiologists. In addition, there was a critical issue with the items of the aforementioned surveys, as they were limited to the clinical practices of surgeons, thereby excluding other important aspects such as perioperative pain management, management of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and intraoperative anesthetic management. Owing to these limitations, it is likely that the aforementioned surveys did not accurately reflect the actual implementation rate of ERAS in South Korea, which emphasizes a multidisciplinary approach. To address this, we conducted a Web of Science search for studies published in South Korea with the title containing the phrase “enhanced recovery after surgery.” As a result, a total of 34 studies were retrieved. Of these, 16 that did not specifically focus on the effects of ERAS were excluded. Additionally, one study was conducted in a foreign country and another did not include details about the ERAS protocol, leading to their exclusion. Finally, the remaining 16 studies were analyzed [11-26]. Table 1 presents the authorship status of anesthesiologists in these studies, along with the inclusion of ERAS items related to the field of anesthesiology. Among the studies examined, general surgery was the most common department (75%), with colorectal surgery (n = 5) and gastrectomy (n = 4) being predominant. With respect to authorship, only four studies (25.0%) included an anesthesiologist as a coauthor. Multimodal analgesia was the most frequently included item related to anesthesiology (68.8%), and half of the studies included reduced fasting time and intraoperative hypothermia prevention. However, intraoperative fluid restriction was included in five studies (31.3%) and multimodal PONV prophylaxis in only two studies (12.5%). The limited involvement of anesthesiologists may reflect poor communication and collaboration, which will be further discussed as a major barrier to ERAS implementation.

Participation of Anesthesiologists and Inclusion of ERAS Items Related to the Field of Anesthesiology in ERAS-Related Studies Conducted in South Korea

Furthermore, ERAS has primarily been introduced by individual researchers rather than by institutions or academic societies, and there has been a lack of organized effort related to its implementation in South Korea. This can be attributed to the lack of policy support, especially the absence of financial incentives, when considering South Korea’s unique healthcare environment. Although the ERAS program can eventually reduce healthcare costs [27], it initially requires the augmentation of additional personnel to provide a bundle of care. In the Korean health insurance and reimbursement system, it can be difficult to receive compensation for this initial cost investment; therefore, ERAS does not appear to be actively implemented at the institutional level.

BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTING ERAS IN SOUTH KOREA

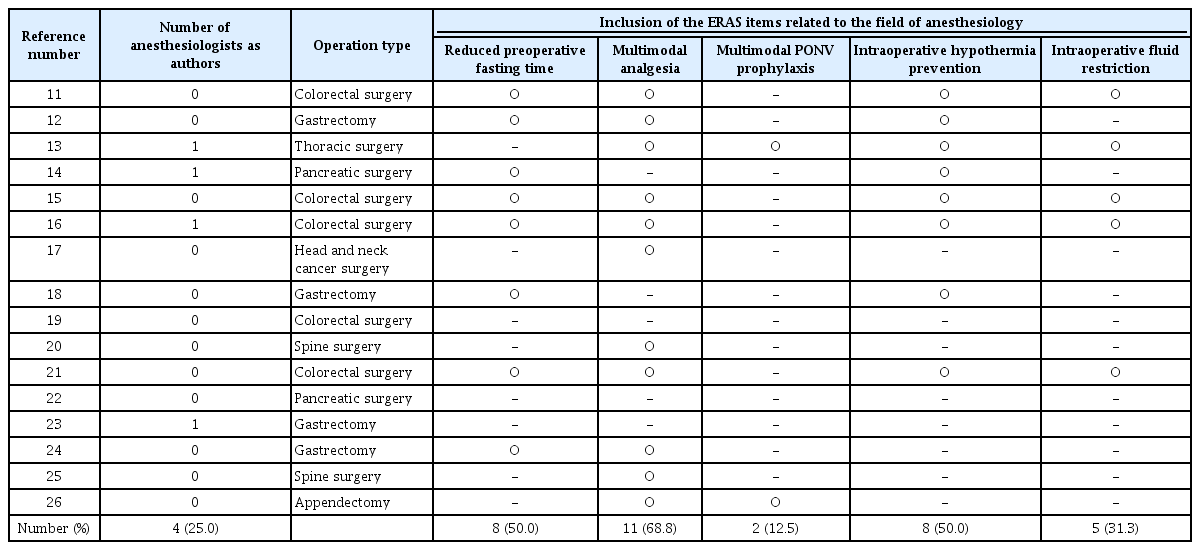

To ensure the successful implementation of ERAS, it is crucial to identify the barriers to its implementation. There have been several reports related to the barriers encountered in the implementation of ERAS [28]. In one systematic review on this issue, the commonly mentioned barriers to ERAS implementation were resistance from healthcare professionals, resistance from patients, limited resources, rotating staff and residents, misconceptions about the difficulty of implementing ERAS, and a perceived lack of evidence [28].

The process of implementing the ERAS program in colorectal surgery at seven hospitals affiliated with the University of Toronto can serve as an exemplary case regarding the adoption of ERAS [29]. Based on the knowledge-to-action cycle they utilized, their implementation strategy followed a five-step process. First, they identified the problems related to ERAS implementation in the current situation. Second, they established an institution-specific ERAS protocol. Third, barriers to ERAS implementation were addressed. Fourth, they established a tailored implementation strategy for ERAS. Finally, they developed an audit and feedback system for ERAS [29]. During this process, they conducted structured interviews with perioperative team members to investigate the barriers to ERAS implementation. The key barriers identified were lack of manpower, poor communication and collaboration, resistance to change, and patient factors [30]. They established strategies to overcome these barriers [31], and as a result, the implemented ERAS program significantly reduced postoperative complications after colorectal surgery [3]. Another recent study conducted in China reported a shortage of medical resources, outdated concepts, poor communication and collaboration among multidisciplinary team members, and a lack of policy support as major barriers to ERAS implementation, similar to the aforementioned findings [32]. Based on the domains used in the aforementioned systematic review concerning barriers to implementing ERAS, we compiled the findings from relevant studies published after the review in Table 2 [28,32-34]. As we thought that these factors also serve as significant barriers to the introduction of ERAS in South Korea, we discuss the major barriers further in the following sections.

Lack of manpower and policy support

Although ERAS has the potential to reduce medical costs by reducing postoperative complications and length of hospital stay [27], a lack of manpower can serve as a significant barrier to its introduction and implementation. First, for successful implementation of ERAS, tailored ERAS protocols for each institution’s context need to be established, which requires active discussion among various perioperative members [29]. To facilitate perioperative members' participation in these discussions, they require time flexibility. Second, from the anesthesiologist's perspective, additional staffing is required for aspects such as the preoperative optimization process and multimodal analgesia, including regional analgesia. Third, additional staff are required to operate an ERAS audit program. An ERAS audit program is essential for monitoring compliance, identifying areas for improvement, standardizing care, and evaluating patient outcomes [35,36]. Thus, it plays a crucial role in optimizing the implementation of ERAS protocols. To conduct such a program, personnel must be capable of continuously collecting and analyzing data. Finally, rotating staff and residents have also been cited as barriers to ERAS implementation [28], and those unfamiliar with the ERAS program may decrease their compliance rate. Therefore, periodic education is required to resolve this issue. However, delivering such education requires additional time and labor. There is a lack of manpower in South Korea; thus, 44.4% of the respondents in a survey on ERAS implementation in major hospitals cited the lack of physiotherapists, nurses, and doctors as a major factor preventing the application of programs [10].

Ultimately, to address these issues, policy support is required to facilitate the implementation of ERAS in clinical practice. Policy support can encourage healthcare providers and institutions to actively implement ERAS programs [37]. These include financial incentives, recognition programs, and performance-based bonuses. By offering these benefits, policy support motivates healthcare providers to embrace and adhere to ERAS programs. Furthermore, such policy support can enable more effective allocation of resources, such as funding and staffing, to support the implementation of ERAS programs in routine clinical practice. Adequate resources are essential for training healthcare providers, implementing necessary infrastructure changes, and monitoring program compliance. In addition, to formulate policies that can support ERAS implementation, it is necessary to evaluate its cost effectiveness. Although several studies on the cost-effectiveness of ERAS have been reported in other countries [38-42], such research has yet to be published in South Korea. Future studies are needed to assess whether the application of ERAS is economically viable within the Korean healthcare environment, and such studies could contribute to policy support for ERAS.

Poor communication and collaboration

The ERAS program involves a team-based approach with healthcare providers from different departments working together to optimize postoperative outcomes. The multidisciplinary team included surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, dietitians, and other healthcare professionals. By collaborating and sharing expertise, a team can develop and implement comprehensive care plans that address all aspects of a patient's perioperative journey (Fig. 1) [43]. However, perioperative care was traditionally provided in isolated service "expertise silos," meaning various perioperative members typically operated solely within their own areas of expertise, with little to no collaboration across different specialties [44]. In a structured interview study conducted in five low- and middle-income countries, fragmented perioperative care pathways were identified as one of the key barriers contributing to poor perioperative care [45]. In contrast, interprofessional communication and collaboration have been reported as key facilitators of ERAS implementation [30,46].

A schematic diagram describing the relationship between interprofessional collaboration and patient recovery after surgery. When there is considerable distance and limited interconnection among professions, surgical patients face a higher risk of “falling” into perioperative stress until they reach recovery (above). Conversely, with robust interprofessional collaboration and communication, patients can minimize exposure to perioperative stress and achieve faster and enhanced recovery (below).

Although there has been little mention of the fragmented perioperative care pathway in South Korea, this issue can be inferred from the ERAS-related studies reported thus far. As mentioned earlier, items related to the roles of anesthesiologists were very limited in surveys on ERAS implementation conducted in South Korea [8-10]. The authors of a survey on the attitudes of hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgeons toward ERAS protocols cited inadequate cooperation with various departments, particularly anesthesiology, as one of the reasons for poor implementation [9]. Moreover, in the aforementioned studies that focused on ERAS in South Korea (Table 1), the participation of anesthesiologists was relatively low. Considering the significant role of anesthesiologists in ERAS, this lack of involvement could be cautiously interpreted as evidence of poor communication in perioperative care.

Resistance to shifting away from outdated concepts

Evidence-based medicine is a fundamental principle of ERAS, with ERAS programs comprising several evidence-based perioperative care elements. Evidence-based perioperative care has the potential to improve postoperative recovery. Nevertheless, adherence in clinical practice remains inconsistent and falls short of the desired level. However, in clinical practice, it is common to make decisions based not only on evidence but also on experiences or traditional practices passed down by senior colleagues. Sometimes, these experiences may conflict with evidence-based recommendations, leading to resistance to evidence-based guidelines [47]. A review of previous studies quantifying the time lag between the emergence of new concepts and real-world applications suggests a 17-year gap [48].

A prominent example of anesthesiologists' resistance to shifting away from outdated concepts is prolonged preoperative fasting. Several guidelines have already suggested a shortened preoperative fasting time of clear liquids up to 2 h before induction of anesthesia [49-51]. However, most hospitals in South Korea adhere to the traditional practice of preoperative midnight nil per os (NPOs). There is no evidence supporting the necessity of a preoperative fasting time of more than 8 h for clear fluids in elective surgical patients, and implementing a shortened preoperative fasting time does not require additional resources. In a survey of Korean gastric surgeons, all patients fasted beginning no later than midnight before surgery; however, only 10.1% were administered carbohydrate-rich drinks before surgery [8]. Similarly, in hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery, only 3-5.6% of cases followed the ERAS guidelines, and the authors noted that it is difficult to change traditional experience-based practice [9]. This resistance to evidence-based perioperative care can be attributed to Korean anesthesiologists’ adherence to traditional practices.

Patient factors

In addition to the aforementioned healthcare provider-related factors, patient-specific risk factors can pose obstacles to ERAS implementation. The risk profile for postoperative recovery can influence compliance with ERAS programs, thereby affecting their effectiveness. In a study conducted on colorectal surgery, a higher American Society of Anesthesiologist physical status classification was significantly associated with lower compliance with the ERAS program [52]. Similarly, a study focusing on patients undergoing laparoscopic distal gastrectomy in South Korea found that a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification and advanced age were significantly associated with lower compliance with the ERAS program [53]. Another study reported a significant association between ERAS program failure and CR-POSSUM Score, a predictive tool for postoperative outcomes in colorectal surgery [54].

In high-risk older adult patients or those with multiple comorbidities, the potential benefits of implementing an ERAS program to reduce perioperative stress and decrease the risk of postoperative complications are likely to be more significant than in healthy patients [55]. Furthermore, ERAS has been reported to have a positive impact on postoperative recovery in emergency surgeries, which are generally considered to have a higher risk than elective surgeries [56]. However, in most prospective clinical trials comparing ERAS with conventional care, the proportion of elderly patients was relatively small, and high-risk patients often demonstrated lower compliance with the ERAS program [52]. This made it challenging to assess the full effectiveness of the ERAS programs in these patient populations. It is crucial to overcome these challenges and apply the ERAS program with a broader range of surgical patients to improve postoperative recovery.

Additionally, patient resistance to the ERAS program has been cited as a barrier to its implementation [28]. All of the three aforementioned surveys in South Korea cited a lack of awareness of ERAS among patients as a major obstacle to its implementation [8-10]. This is particularly relevant in Korea, where the benefits of the ERAS program are not yet well known to the general public. The program has primarily been conducted in the form of research studies, suggesting that there could be significant patient resistance. To resolve this issue, it is essential to not only conduct research on the efficacy of ERAS but also promote its positive effects to the general public.

ROLE OF KOREAN ANESTHESIOLOGISTS IN OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO ERAS IMPLEMENTATION

Korean anesthesiologists can play a pivotal role in overcoming barriers to ERAS implementation. To achieve this, the following are required. First, Korean anesthesiologists should be aware of the significant impact their clinical practices can have on postoperative recovery and should identify areas for improvement in their current practices based on recent evidence. In particular, there is an urgent need to change the current perioperative practices, such as prolonged preoperative fasting and opioid-based pain management, which are far from supported by scientific evidence, using the latest evidence-based approaches. Second, active communication and collaboration with other departments are required to incorporate the role of anesthesiologists beyond intraoperative anesthetic management into the ERAS program. The preoperative optimization process and multimodal opioid-sparing analgesia, which are essential components of ERAS, require collaboration with other departments. To achieve this, we need to provide accurate information on the extended role of anesthesiologists in perioperative medicine and their impact on postoperative recovery in other departments. Third, Korean anesthesiologists need to develop the capacity to invest resources in improving postoperative recovery through the efficient allocation of limited resources. As administrators of the operating room management, anesthesiologists can optimize operating room efficiency, reduce medical costs, and provide financial benefits [57]. Finally, Korean anesthesiologists should not only focus on the introduction of ERAS but also establish strategies to enhance compliance after its implementation. To achieve this, collaboration with other departments is essential to develop institution-specific ERAS protocols tailored to local contexts. The establishment of local context-specific protocols has been reported to facilitate successful ERAS implementation [28]. In addition, the creation of customized ERAS protocols that consider patient-specific factors is crucial. As previously mentioned, patient factors have been identified as significant barriers to ERAS compliance. Therefore, Korean anesthesiologists should conduct large-scale prospective studies across diverse patient groups to assess the effectiveness of personalized ERAS protocols. Another method of improving ERAS compliance is to adopt an audit and feedback system. The ERAS® Interactive Audit System, developed by the ERAS® Society, is a representative example of such a system [36]. Introducing an audit system can help monitor ERAS effectiveness, identify areas for improvement, standardize care, and evaluate patient outcomes. Compliance with ERAS can be enhanced by incorporating an audit and feedback system, leading to better patient outcomes and improved perioperative care in South Korea [35].

Furthermore, Korean anesthesiologists should make an effort to garner support for ERAS implementation at the academic society or institution level. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Enhanced Recovery Partnership Programme (ERPP) was introduced in 2009 by national agencies to support the implementation of ERAS programs for various surgery types, resulting in approximately 24,000 patients already recorded in the ERPP database in 2012 [5]. In Alberta, Canada, a fully integrated healthcare system named Alberta Health Services introduced a demonstration project implementing the colorectal ERAS guidelines and included more than 75% of all colorectal surgeries in the province up to 2015 [58]. In addition, ERAS adoption is rapidly gaining momentum in academic institutions and societies across Asia. The Medical City in the Philippines and Tan Tock Seng Hospital in Singapore were designated as the first ERAS Centers of Excellence in Asia in 2016 [59]. Both have played key roles in spearheading ERAS initiatives in their respective countries and in the broader Asian region. In 2019, these institutions collaborated with the ERAS® Society to organize the first Asian ERAS Congress. Recently, Japan joined the ERAS® Society as a new chapter, signifying its intent to actively expand the implementation of ERAS. In China, ERAS has been identified as a vital component of perioperative medicine [60]; the first ERAS group was established there in 2015 [61], and several guidelines have subsequently been published [62,63]. Overall, both institutional and academic endorsement of ERAS in Asia are on an upward trajectory. Korean anesthesiologists should not be limited to the role of individual researchers but must also make organizational efforts to introduce and establish ERAS in South Korea.

From this perspective, it is noteworthy and highly welcome that the recent collaboration between the Korean Society of Anesthesiologists (KSA) and the Korean Surgical Society (KSS) has established a cooperative system for institutional improvements and reached an agreement to propose a pilot project for new incentive fees related to ERAS performance to the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare [64]. The first meeting of practitioners from the KSA and the KSS for this purpose took place on August 30, 2023. Additionally, under the current leadership of the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition, Korean ERAS guidelines are being developed for gastric, colorectal, and hepatobiliary pancreatic cancer surgeries. Members of the KSA are also responsible for developing anesthesia-related items within these guidelines. These collective efforts at the academic and societal levels are likely to contribute significantly to the establishment and application of ERAS in the Korean medical landscape.

The challenges ahead for anesthesiologists, as described by authors from our neighboring country, China, hold significant implications for us as well [60]. They delineated several forthcoming tasks for anesthesiologists, which encompass the following aspects. First, they should gain precise comprehension of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine in other departments. Second, they should actively engage in the ERAS program and play a pivotal role in its implementation. Third, they should assume a leadership position in postoperative multidisciplinary team pain management. Fourth, they should augment the educational content on perioperative medicine in the resident training program. Finally, medical research on perioperative medicine should be enhanced. These tasks align with the roles of Korean anesthesiologists mentioned earlier, and such effort will not only act as a facilitator in implementing ERAS but also ultimately expand the role of anesthesiologists in perioperative medicine in South Korea.

CONCLUSION

Although the ERAS has demonstrated remarkable benefits, its effective implementation in clinical settings in South Korea is challenging. Such barriers include a lack of manpower and policy support, poor communication and collaboration among multidisciplinary teams, resistance to shifting away from outdated concepts, and patient-specific risk factors. To overcome these barriers and improve postoperative recovery, Korean anesthesiologists can play a pivotal role by adopting evidence-based practices, enhancing interdisciplinary collaboration, and advocating for policy support. By addressing these challenges, ERAS implementation in South Korea could be more successful, leading to improved patient outcomes and enhanced perioperative care. Efforts to implement ERAS will expand the scope of perioperative medicine in South Korea.

Notes

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Writing - original draft: Soo-Hyuk Yoon. Writing - review & editing: Ho-Jin Lee. Conceptualization: Ho-Jin Lee. Supervision: Ho-Jin Lee.