Tension hydrothorax induced by malposition of central venous catheter -A case report-

Article information

Abstract

Central venous catheterization is a useful method for monitoring central venous pressure and maintaining volume status. However, it is associated with several complications, such as pneumothorax, hydrothorax, hemothorax, and air embolism. Here we describe a case of iatrogenic tension hydrothorax after rapid infusion of fluid into the pleural space, following the misplacement of an internal jugular vein catheter. Despite ultrasonographic guidance during insertion of the central venous catheter, we were not able to avoid malposition of the catheter. The patient went into hemodynamic compromise during surgery, necessitating chest tube drainage and a mechanical ventilator postoperatively. This case shows that central venous catheter insertion under ultrasonographic guidance does not guarantee proper positioning of the catheter.

INTRODUCTION

Central venous catheter insertion is a common procedure in anesthetic practice. Central venous catheters have been used as important access tools in patients requiring large amounts of fluid resuscitation or measurement of central venous pressure (CVP). However, their usage is associated with several complications. Common mechanical complications are arterial puncture, malposition-induced hematoma, and pneumothorax, which occur in 5–19% of all cases [1]. Complications immediately following the procedure are gradually decreasing nowadays owing to improvements in procedural techniques and equipment [2,3]. Hydrothorax is a rare complication of central venous catheter insertion with an incidence 0.4–1% [4]. In some cases, it can lead to tension hydrothorax resulting in respiratory failure, hemodynamic compromise, and cardiopulmonary collapse. Hydrothorax caused by malposition of the central venous catheter into the thoracic cavity may lead to severe adverse results, with mortality rates up to 74% [5]. Ensuring adequate positioning of a central venous catheter is necessary in order to minimize morbidity and mortality. In this report, we describe a case of tension hydrothorax, which led to hemodynamic compromise due to malposition of the central venous catheter, requiring immediate chest tube insertion and mechanical ventilation care. Although we used ultrasonographic guidance during central venous catheterization, it did not guarantee proper position of the catheter.

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old woman with cholangiocarcinoma was admitted for elective left hemihepatectomy. She was of American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification 2 and had a weight of 60 kg and height of 150 cm. She had been on hypertension medications for 10 years. There were no specific findings upon physical examination, chest radiography, electrocardiogram, or blood test before surgery.

After induction of anesthesia, a central venous catheter was inserted to correct volume loss and monitor volume status. A right internal jugular approach was used with anatomical landmarks, and the Seldinger technique was used with ultrasound guidance. The puncture site was 3 cm above the clavicle between the lateral and medial portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Two attempts were made by a resident to cannulate the right jugular vein, but both failed. A third attempt to cannulate the internal jugular vein was performed by a skilled anesthesiologist using a 7 Fr catheter (ARGON critical care system, CVP catheter, triple lumen, 15 cm). There was no arterial puncture nor air aspiration during this attempt. After cannulating the internal jugular vein, free blood return was observed from all three catheter ports. All ports were easily flushed. The intravenous catheter in the lumen was visible on ultrasonography, but the exact location of the catheter tip was not verified. The central venous catheter was fixed at a length of 12 cm. The puncture site was covered with wound dressing. The proximal lumen (4 cm away from the catheter tip) was used to monitor CVP. The waveform of the CVP was optimal. We connected the colloid solution at the middle port (2 cm away from the catheter tip) with crystalloid solution at the distal port (located at the catheter tip). CVP measurement indicated optimal pressure, but free blood return was not observed from the middle and distal ports at this time. As we thought that the catheter tip may have attached against the venous wall, we decided to use all three ports. Arterial blood gas test results at the time with FiO2 of 0.5 were: pH 7.34, PCO2 34 mmHg, PO2 244 mmHg, SaO2 98%, HCO3− 18.4 mmol/L, BE −6.6 mmol/L, Hb 10.7 g/dl, and Hct 31%.

We used the restrictive fluid infusion method to minimize CVP during hepatectomy. After four hours of anesthesia induction, the patient’s blood pressure (BP) started to decrease steadily to 80/57 mmHg. We started to infuse 4 μg/kg/min of dobutamine through the distal port, but we could not maintain a stable BP with dobutamine, and therefore added a norepinephrine infusion. At this time, 1,000 ml of fluid was given to the patient, and 260 ml of blood and 130 ml urine flowed from the patient. We then started rapid fluid infusion through the middle port using a rapid infusion system (FMS 2000, Belmont), but the patient rapidly went into hemodynamic instability and her BP dropped to 68/48 mmHg. A 10 μg bolus of epinephrine was injected, but there was no change. Severe bradycardia was observed, and tidal volumes showed a significant decrease. The patient’s maximum inspiratory pressure suddenly rose to 40 mmHg. Lung auscultation revealed the absence of breath sounds on the right side of the chest. Fluid regurgitation through both the middle and distal ports of the central venous catheter followed. Severe expansion of the patient’s diaphragm led us to suspect it was the effect of tension. A chest tube insertion was performed immediately by an operator (intercostal insertion in the midaxillary line of the 10th intercostal space), and 3.5 L of clear fluid was drained under pressure from the interpleural space. A similar amount of fluid was given to the patient through the internal jugular vein catheter. Arterial blood gas test results at that time, with FiO2 of 1.0 were: pH 7.10, PCO2 48 mmHg, PO2 206 mmHg, SaO2 98%, HCO3− 13.5 mmol/L, BE −14.6 mmol/L, Hb 8.5 g/dl, and Hct 25%. As we noticed the tip of central venous catheter was located in the pleural space, we immediately stopped infusion through the central venous catheter. Drug infusion was transferred to the peripheral line on the right arm of the patient, and the central venous catheter was removed. A chest radiography had been ordered at the time, but due to technical reasons, it was not performed until the central venous catheter was removed. We inserted an 18 G catheter in both saphenous veins and started rapid infusion of fluid and transfusion. The patient’s BP and oxygen saturation increased to 130/85 mmHg and 100%, respectively. We estimated that the proximal port of the catheter was inside the vessel, and other two ports were located in the interpleural space. No backflow from the distal and middle lumen indicated its malposition.

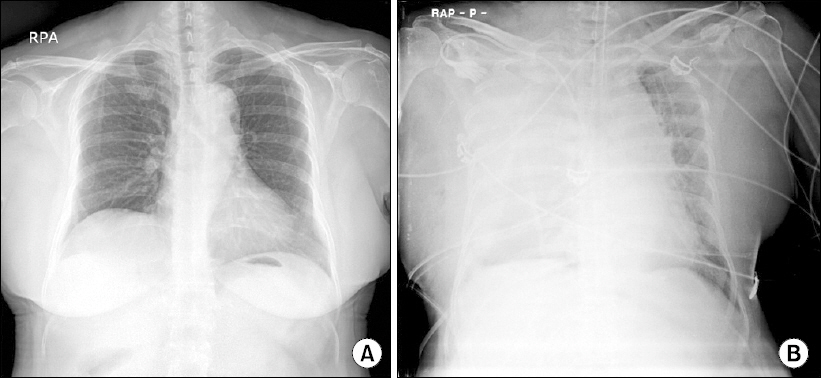

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) after operation to continue mechanical ventilation support. The patient’s BP remained stable at 110/70 mmHg after 0.4 μg/kg/min of norepinephrine, and the patient’s oxygen saturation was 100% on pressure control mode with a FiO2 of 0.5. Postoperative radiography showed severe pulmonary edema and pulmonary effusion in the right lung (Fig. 1). Ventilation support was continued and her condition improved steadily. Low-pressure suction and furosemide injection were applied constantly. The ventilator mode was changed to SIMV on postoperative day (POD) 1. On POD 2, 700 ml of fluid was drained after percutaneous catheter drainage insertion. Extubation occurred on POD 3, once breathing discomfort decreased, and the patient was discharged on POD 15.

DISCUSSION

The central venous catheter is a useful tool for delivering fluids, drugs, and monitoring the volume status. Inadequate positioning of the central venous catheter causes complications like pneumothorax, hemothorax, hydrothorax, arterial puncture, and air embolism. Hydrothorax is a rare complication described in approximately 0.5% adult cases with central venous catheterization [4]. This complication usually occurs in cases of progressive vascular erosion of an initial intravascular catheter, poor positioning of the tip, or loose catheter fixation.

There are many case reports of delayed hydrothorax occurring after migration of a central venous catheter during ICU care. In most cases, however, the amount of pleural effusion was relatively less and was not life threatening.

Life-threatening tension hydrothorax during ICU care was reported by Maroun et al. [6] in 2013. A 49-year-old woman with a seizure and mental change was intubated and central venous catheterization was performed in the ICU. A normal saline bolus was administered to treat hypotension, but her BP decreased steadily and she became hypoxic and cyanotic with oxygen saturation at 84% on 100% oxygen. A tension hydrothorax was detected on a chest radiogram. The patient achieved hemodynamic stability with immediate removal of the central venous catheter and emergent pleural tap.

In our case report, we described an iatrogenic hydrothorax followed by inadequate positioning of the internal jugular vein catheter, which led to tension crisis during surgery. Despite ultrasound guidance, a part of the central venous catheter went into the wrong location. There has been a report describing the position detection of an already functioning central venous catheter, using transthoracic echocardiogram. They found that the tip of the catheter was not in proper position in up to 40% of cases [7]. Without noticing the malposition of the central venous catheter, we infused inotropic agents and used rapid fluid infusion to treat low BP. We think that there was some damage to the wall of the internal jugular vein, and formation of a focal hematoma during the several attempts of catheterization. Blood regurgitation from the distal and middle posts was first suspected to be blood from the hematoma, preventing us from noticing that the central venous catheter was fixed in the wrong position.

The absence of free flow on aspiration from the lumen of a central venous catheter should not be ignored, as it suggests inadequate positioning of the catheter. In addition, it must be considered that normal CVP waveform does not guarantee proper position of all lumens of the central venous catheter. Emergency chest radiographs are necessary in case of negative aspiration of blood after the insertion of the central venous catheter. In our case, we should have re-ensured proper position of the central venous catheter using ultrasonography or chest radiography following detection of the loss of regurgitation of both middle and distal lumens.

This report emphasizes the importance of ensuring correct positioning of the central venous catheter using aspiration of venous blood and offensive application of radiography, and, in difficult catheterization, ultrasound guidance. If using ultrasonographic guidance, proper positioning of the central venous catheter should be ensured by searching for the entire catheter, including the tip.