INTRODUCTION

Postoperative sore throat (POST) is a common adverse event after surgery under general anesthesia requiring tracheal intubation; its incidence ranges from 14% to 54% [

1-

4]. Since most associated symptoms resolve spontaneously without treatment, anesthesiologists have historically not focused on finding a way to prevent and treat POST. However, POST could adversely affect patient satisfaction and activity after hospital discharge [

4,

5]. Therefore, for the quality of anesthesia care, POST needs to be actively prevented.

Lidocaine, a pharmacological intervention, has often been used for the prevention of POST in common clinical practice. While a recent systematic review showed this practice to be generally beneficial, the outcome appears to vary according to the route of administration [

6]. Especially, lidocaine jelly applied on the endotracheal tube (ETT) was believed to be beneficial due to the lubricating and local anesthetic effects, although its effectiveness for the prevention of POST remains controversial [

7-

9].

Various non-pharmacological interventions, such as the change of tube size or cuff design, have also been investigated to prevent POST. Recently, Seo et al. [

10] showed that the incidence of POST and vocal cord injuries with double-lumen endobronchial tube decreased by thermal softening of the tube, which is an established method used to decrease trauma to the nasal passages during nasotracheal intubation [

11]. This non-pharmacological intervention has seldom been studied for the prevention of POST, particularly in orotracheal intubation with single-lumen ETT.

We hypothesized that a combination of these pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions may be more effective for the alleviation of POST than either intervention alone. The primary objective of this trial was to determine whether this combined treatment could reduce the severity of POST. The secondary objective was to assess the incidence of sore throat and hoarseness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective, randomized controlled trial was approved by our Institutional Review Board (CNUH 2016-244) and registered at the Clinical Research Information Service (

http://cris.nih.go.kr, KCT000216). We obtained written informed consents from all patients aged 20-70 yr who were classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists as physical status I-III scheduled for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy or laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy. A Mallampati test was performed after patient enrolment. Based on our exclusion criteria, we excluded patients with: 1) anticipated difficult intubation (Mallampati class ⼠3); 2) previous throat pain or a hoarseness history; 3) a recent history of upper respiratory infection; 4) a habit of smoking; 5) cervical spine disease; and 6) a history of lidocaine allergy. Patients who required repetitive attempts, a stylet, or the backward upward rightward pressure (BURP) maneuver at intubation were also excluded during the analysis process.

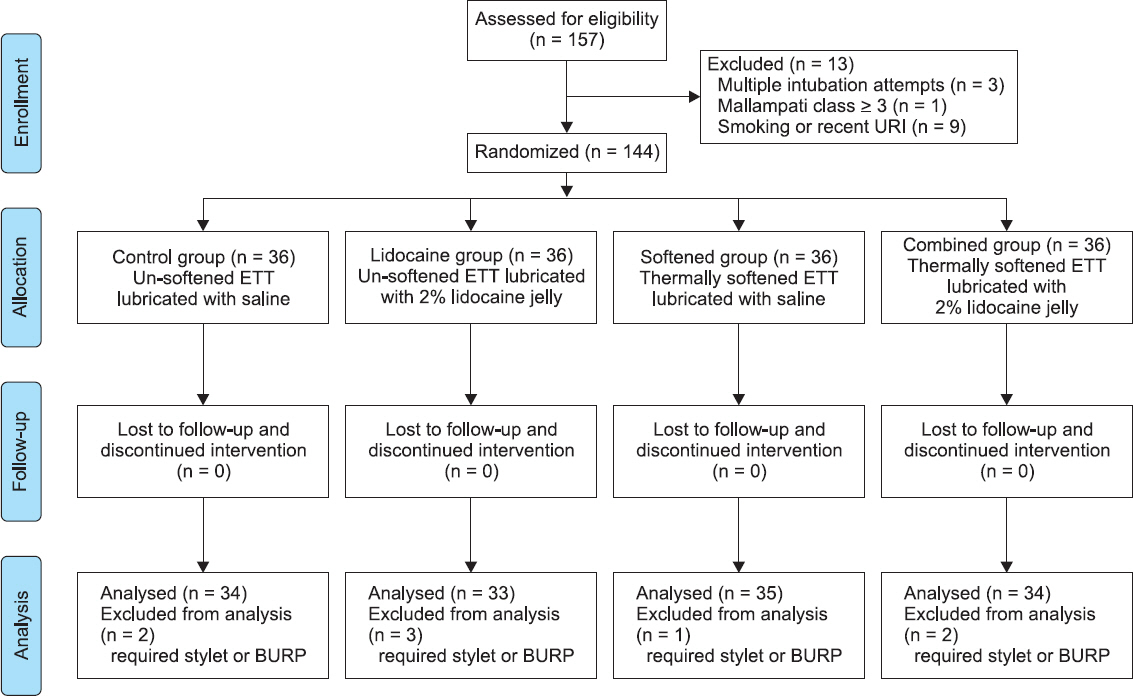

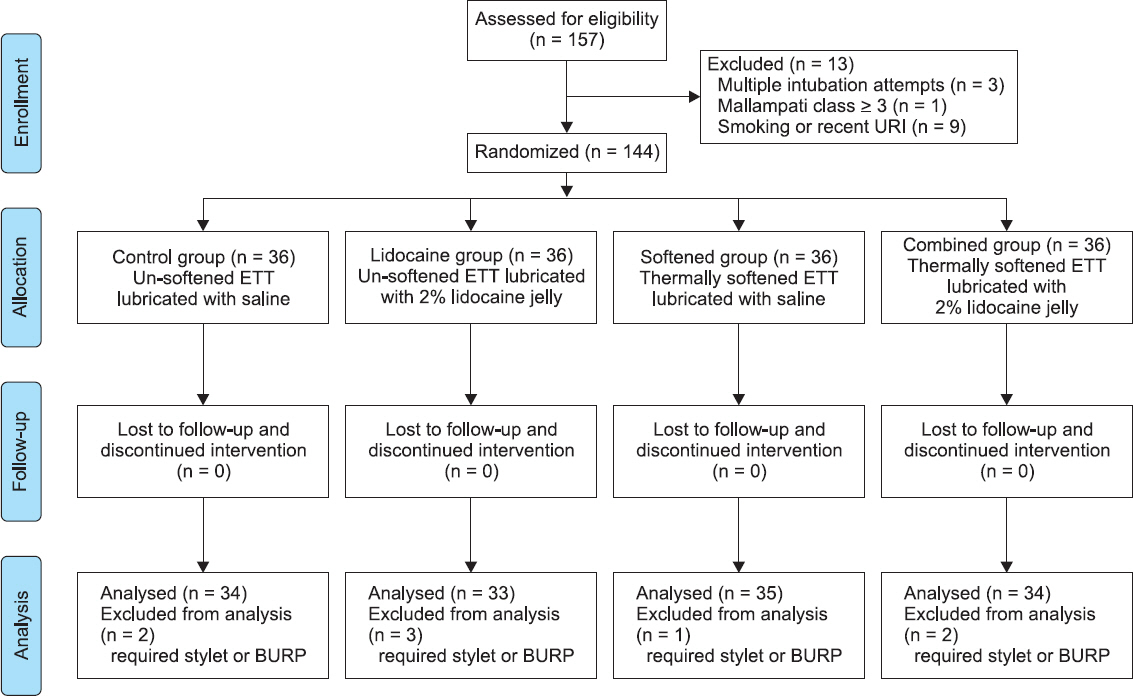

From September 2016 to February 2017, 157 patients were screened, of which 13 were excluded according to the above exclusion criteria. A total of 144 patients were allocated to 4 groups (36 patients for each group). Eight patients were excluded in the analysis process because of the use of BURP maneuver during intubation. In all other patients, the trachea was intubated without difficulty and with no patient movement. Thus, 136 patients in total were included for data analysis (

Fig. 1). The demographic characteristics of the four groups were comparable (

Table 1), and the variables associated with intubation did not differ among the groups (

Table 2).

Table 1

|

Variable |

Control (n = 34) |

Lidocaine (n = 33) |

Softened (n = 35) |

Combined (n = 34) |

|

Sex (M/F) |

12/22 |

11/22 |

10/25 |

8/26 |

|

Age (yr) |

44 Âą 13 |

43 Âą 14 |

47 Âą 12 |

46 Âą 12 |

|

Weight (kg) |

62 Âą 8 |

62 Âą 12 |

63 Âą 11 |

63 Âą 9 |

|

Height (cm) |

163 Âą 7 |

162 Âą 7 |

162 Âą 7 |

161 Âą 7 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

23 Âą 3 |

23 Âą 4 |

24 Âą 3 |

24 Âą 3 |

|

ASA physical status (I/II/III) |

16/12/6 |

16/9/8 |

15/12/8 |

14/12/8 |

|

Remifentanil dosage Îźg/kg/min) |

0.044 (0.036, 0.052) |

0.044 (0.035, 0.054) |

0.039 (0.035, 0.052) |

0.043 (0.037, 0.050) |

Fig. 1

Consort flow study diagram. ETT: endotracheal tube, URI: upper respiratory infection history, BURP: backward upward rightward pressure.

Table 2

Variables Associated with Tracheal Intubation

|

Variable |

Control (n = 34) |

Lidocaine (n = 33) |

Softened (n = 35) |

Combined (n = 34) |

P value |

|

Mallampati class (I/II) |

24/10 |

24/9 |

24/11 |

23/11 |

0.970 |

|

Cormack-Lehane grade (I/II) |

29/5 |

28/5 |

27/8 |

27/7 |

0.774 |

|

Duration of intubation (min) |

70 (60, 100) |

70 (50, 97) |

70 (55, 90) |

75 (60, 98) |

0.632 |

|

Tube cuff pressure (cmH2O) |

22 (22, 23) |

22 (22, 23) |

22 (22, 22) |

22 (22, 23) |

0.876 |

All patients were randomly assigned to one of the four groups: Control group (un-softened ETT lubricated with saline); Lidocaine group (un-softened ETT lubricated with 2% lidocaine jelly); Softened group (thermally softened ETT lubricated with saline); and Combined group (thermally softened ETT lubricated with 2% lidocaine jelly). According to the allocated group, all ETTs (TaperGuardâ˘, Covidien, Ireland) were pretreated by an independent assistant. After deflating a cuff, a distal half portion of ETT was soaked in sterile normal saline (at 40ËC for thermally softened ETT groups and at room temperature for un-softened ETT groups) for 5 min before tracheal intubation. Maintaining the ETTs at 40ËC for 5 min sufficiently softened the tube and the softness was well maintained until the endotracheal intubation. The ETT was lubricated with 2% lidocaine jelly (Korea Pharma, Korea) or saline from the distal margin of the cuff to 2 cm above the proximal margin of the cuff 1 min before tracheal intubation. Allocation to each study group was randomized according to a pre-assembled list randomly generated using the Excel program. All patients were kept blinded to the group to which they were assigned. General anesthesia was induced by propofol and remifentanil with routine monitoring, and rocuronium 0.8 mg/kg was administered subsequently. Intravenous lidocaine was not injected to rule out the impact on results.

Tracheal intubation was performed with pretreated ETT (8 mm internal diameter for men, 7 mm for women) using a Macintosh laryngoscope. The cuff of the ETT was inflated with air, and the intracuff pressure was immediately adjusted to 20 to 25 cmH2O using a manometer (VBM, Germany). Laryngoscopy grade (Cormack-Lehane grade), endotracheal tube cuff pressure, and duration of intubation were recorded by an independent assistant. Desflurane or sevoflurane was used for the maintenance of anesthesia with remifentanil 0.05-0.1 Âľg/kg/min. At the end of surgery, remifentanil infusion was stopped, and residual neuromuscular blockade was antagonized by pyridostigmine and glycopyrrolate. When the patient was fully awake, the cuff of the ETT was fully deflated and the ETT was removed smoothly.

Upon arrival in the recovery room (time 0 h), another investigator, who was blinded to the group allocation, assessed the incidence of POST using a direct question such as âDo you have pain or discomfort in the throat?â [

12]. This question was asked after confirming that the patient mental status was clear. In addition, the degree of sore throat severity was measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS), where 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst pain imaginable [

13]. After this assessment, the patient received a bolus administration of fentanyl 100 Âľg and propacetamol 2 g, followed by an intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA) with fentanyl and propacetamol. IV-PCA with the same regimen was applied until the end of the study (48 h). If additional rescue analgesia was needed, it was recorded. The severity and incidence of POST were assessed at 1, 6, 24, and 48 h after tracheal extubation in the same manner. The occurrence of hoarseness, coughing, and any postoperative complication for 48 h was also assessed.

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation for the present study was based on 0 h VAS scores in a pilot study (n = 8 in each group, total n = 32). According to the pilot study, we calculated the variance (Ď2) = 0.05792114 (effect size = 0.248). With a power of 80% at a significance level of 0.05 for one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), a total sample size of 132 was calculated (33 patients for each group). Taking into account potential dropouts, a total of 144 patients were allocated to 4 groups (36 patients for each group). All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (SPSS 18.0, IBM Corp., USA). Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Severity of POST and demographic data (age, weight, height, and body mass index) were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. Remifentanil dosage, duration of intubation, and tube cuff pressure were analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Chi-square or Fisherâs exact test was used for comparing the incidence of POST and other binary/categorical variables. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All results are expressed as the mean Âą standard deviation, median (1Q, 3Q), or numbers (percentage).

RESULTS

No significant difference was observed in the severity of POST at all time points (

Table 3).

Table 3

Severity of Postoperative Sore Throat after Extubation (Visual Analogue Scale)

|

Time |

Control (n = 34) |

Lidocaine (n = 33) |

Softened (n = 35) |

Combined (n = 34) |

P value |

|

0 h |

1.8 Âą 1.3 |

1.9 Âą 1.3 |

1.7 Âą 1.2 |

1.3 Âą 1.6 |

0.217 |

|

1 h |

1.1 Âą 1.1 |

1.1 Âą 1.0 |

1.2 Âą 1.0 |

0.9 Âą 1.0 |

0.581 |

|

6 h |

1.0 Âą 0.2 |

0.2 Âą 0.9 |

0.1 Âą 0.5 |

0.5 Âą 1.1 |

0.063 |

|

24 h |

0.2 Âą 0.8 |

0.1 Âą 0.4 |

0.1 Âą 0.2 |

0.1 Âą 0.3 |

0.375 |

|

48 h |

0 Âą 0 |

0 Âą 0 |

0.0 Âą 0.2 |

0 Âą 0 |

0.410 |

The incidences of POST at 0, 1, 6, 24, 48 h, and 0-48 h (overall) after extubation are presented in

Table 4. The overall incidence of POST was significantly lower in the Combined group (52.9%) than in the Control group (79.4%; P = 0.021), Lidocaine group (81.8%; P = 0.012), and Softened group (82.9%; P = 0.010), whereas no significant difference was found among the Control group, Lidocaine group, and Softened group. Similarly, upon arrival at the recovery room (0 h), the incidence of POST was significantly lower in the Combined group (47.1%) than in the Control group (76.5%; P = 0.013), Lidocaine group (78.8%; P = 0.007), and Softened group (74.3%; P = 0.021), whereas no significant difference was found among the Control group, Lidocaine group, and Softened group. From 1 h after extubation (at 1, 6, 24, and 48 h), the incidence of POST was not significantly different among the groups. The overall incidence of hoarseness did not differ among the groups (14.7% in Control group; 3.0% in Lidocaine group; 2.9% in Softened group; 5.8% in Combined group, P = 0.071). No other postoperative complications were observed in any of the patients.

Table 4

Incidences of Postoperative Sore Throat after Extubation

|

Time |

Control (n = 34) |

Lidocaine (n = 33) |

Softened (n = 35) |

Combined (n = 34) |

P value |

|

Overall |

27 (79.4)*

|

27 (81.8)*

|

29 (82.9)*

|

18 (52.9) |

0.012 |

|

0 h |

26 (76.5)*

|

26 (78.8)*

|

26 (74.3)*

|

16 (47.1) |

0.015 |

|

1 h |

20 (58.8) |

19 (57.6) |

22 (62.9) |

17 (50.0) |

0.749 |

|

6 h |

11 (32.4) |

6 (18.2) |

3 (8.6) |

5 (14.7) |

0.073 |

|

24 h |

4 (11.8) |

3 (9.1) |

4 (11.4) |

2 (5.9) |

0.832 |

|

48 h |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (2.9) |

0 (0) |

0.406 |

DISCUSSION

POST can be the consequence of mechanical injury during the intubating process and mucosal injury by the cuff pressure, leading to inflammatory changes. To reduce such injuries with less cost and effort, we selected two possible preventive interventions that are safe and easy to apply in clinical settings. The present study demonstrated that the combination of thermally softened ETT and 2% lidocaine jelly decreased the overall incidence of POST, and this combination especially reduced POST in the immediate postoperative period after extubation. However, the single method of thermally softened ETT or 2% lidocaine jelly did not prevent POST compared with the control group.

A recent study showed that thermally softened double-lumen endobronchial tube significantly reduced the incidence of POST compared with non-softened tubes [

10]. We expected this thermal softening method to help single-lumen ETT pass through the larynx and trachea more smoothly, and can even be molded to the shape of the trachea. However, in the present study, this non-pharmacological intervention was not effective for the single-lumen ETT. This discrepancy might be due to the different stiffnesses and external diameters of the tubes. Because single-lumen tubes are not as stiff as double lumen tubes and have a smaller external diameter, the beneficial effect of thermal softening for the prevention of POST may not be prominent in single-lumen tubes.

Lidocaine jelly (2%) applied on the tubes as a pharmacological intervention was also not effective in this study. In an earlier study, a comparison between dry tubes and lubricated tubes with 1% cinchocaine jelly suggested that the use of lubricants containing a local anesthetic may be beneficial for the prevention of POST [

14]. However, in other studies [

8,

15,

16], 2% lidocaine jelly did not decrease the incidence of POST, which is a similar result as that of the present study. Lee et al. [

9] even showed that lidocaine jelly applied on the ETT with tapered-shaped cuff increased the overall incidence of POST compared with the control. They attributed this deleterious effect to potentially irritating additives in lidocaine jelly, such as chlorhexidine gluconate (Instillagel, 2% jelly, CliniMed Limited, UK), and suggested that a tapered-shaped cuff might enhance this effect by keeping the lidocaine jelly in a greater contact area than the conventional cylindrical cuff. While the same ETT with a tapered-shaped cuff was used in the present study, we used a different lidocaine jelly that has none of the irritating additives previously identified. In view of the results obtained, 2% lidocaine jelly seems to neither decrease nor increase the incidence of POST when there are no potentially irritating additives.

Neither thermal softening nor 2% lidocaine jelly were effective when used separately in the present study, although a combination of the two interventions surprisingly resulted in a significantly decreased incidence of POST. The mechanism by which this combination reduces POST is not clear. The possible explanation is that a combination of minor effects from both interventions was revealed to be statistically significant in an additive or synergistic fashion. It is likely that an analgesic effect of 2% lidocaine jelly and reduced irritant effect of thermally softened tube act together to reduce sore throat. Regardless of the precise mechanism, the result of the present study demonstrates that the overall incidence of POST may decrease by applying 2% lidocaine jelly on thermally softened ETT.

In the present study, the overall incidence was higher than in previous studies in which the incidence was 40-54% [

1,

2,

4]. This higher incidence seems to be related to the measurement time point. While the first measurement of POST in most previous studies was accomplished one or more hours after the operation, we performed the first measurement immediately after arriving at the recovery room. The selection of this time point (0 h) was made to enable investigation of the effect of preventive interventions before the routine administration of postoperative analgesics. The incidence of POST 1h after operation was about 50-63%, which is comparable to that of previous studies.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, the incidence of POST might be influenced by a fentanyl-propacetamol mixture which has analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties. In the recovery room, these drugs were administered to all patients for postoperative pain control. In fact, the result of this study shows that the initial sore throat symptom of many patients was resolved in one hour after arrival at the recovery room. However, the amount of analgesic administered did not differ among the groups. This could permit a comparison of the effectiveness of different interventions in the present study. Secondly, it was impossible to blind the investigator who performed endotracheal intubation because the difference between room temperature ETTs and thermally softened ETTs was readily apparent, even though the tubes were hidden by opaque bottles until immediately before intubation. In addition, the investigator was able to distinguish between lidocaine jelly and saline. Potential bias was minimized by blinding the investigator who measured postoperative outcomes. Thirdly, we did not record the objective signs of sore throat after surgery, such as the degree of mucosal damage, to reduce health care cost and patientsâ inconvenience. However, subjective symptoms should be sufficient to assess the incidence and severity of POST because it is a self-limiting inflammatory process with/without minor mucosal erosion in most cases. However, with objective data, we might have been able to suggest a clear hypothesis about the benefit of combined interventions.

In conclusion, no difference was observed in the severity of POST. However, 2% lidocaine jelly applied on thermally softened single-lumen ETT reduced the overall incidence of POST. Therefore, this combined intervention could be considered as an alleviating strategy for POST.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.