척추수술후만성통증의 치료

Current strategy for chronic pain after spinal surgery

Article information

Abstract

Failed back surgery syndrome was recently renamed, as chronic pain after spinal surgery (CPSS) by international classification of disease-11. CPSS is a challenging clinical condition. It has a variety of causes associated with preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative periods. Also, psychosocial factors should be considered. Diagnostic tools must be used differently, for each patient. Imaging and interventional nerve block for diagnosis, should be used properly. Strategy of management requires a multidisciplinary approach. The effect of conservative management (medication, interventional management) and invasive procedure (spinal cord stimulator, intrathecal drug delivery system) has been studied by many researchers. However, an evidence-based guide on management of CPSS, remains necessary, and further research is needed. This review focuses on understanding and clinical approaches for CPSS.

서론

척추수술후요통증후군(Failed back surgery syndrome)의 정의는 ‘1회 이상의 척추 수술 이후에도 요통이 지속되고 하지 방사통은 존재하거나 그렇지 않은 상태’로 정의되는 것이 일반적이다[1]. 그러나 질환명에서 드러나는 부정적인 암시로 인해 명칭에 대한 논란이 있어 동시에 여러 명칭을 가진 질환이기도 하다. 수술을 시행한 척추 외과의나 통증 치료를 담당해야하는 통증의사 모두에게 치료가 어려운 질환이며 이는 원인, 진단, 치료, 예후에 대해 각 보고마다 차이가 있어 높은 의학적 근거를 가지는 치료 방법이 아직 명확하지 않기 때문이기도 하다. 이에 본문은 국내 현황에 맞추어 척추수술후요통증후군에 대해 고찰하고 최신의 효과적인 치료에 대하여 소개하고자 한다.

명칭과 정의

척추수술후요통증후군이 포함하는 수술 실패라는 의도하지 않은 암시로 인해 다른 정의와 명칭들이 존재한다. 그 중, 임상 상황에 적절한 기능적 정의는 척추 수술의 결과가 수술 전 기대한 바와 다를 때, 집도의와 환자가 각각 기대한 바가 일치하지 않는 상황이 적합할 것이다[2]. 수술 실패라는 의미를 암시하지 않는 척추후궁절제술후증후군(post laminectomy syndrome), 척추수술후증후군(post spinal surgery syndrome), 요추수술후증후군(post lumbar surgery syndrome) 등의 명칭이 있지만 세계보건기구(World Health Organization)에서 2018년 6월에 발표한 국제질병분류(international classification of disease)-11에 따르면 척추수술후만성통증(chronic pain after spinal surgery)으로 명명된 것을 알 수 있다[3]. 정의는 수술 후 발생한 만성 요통이나 하지 통증이 3개월 이상 지속되거나 재발한 경우이다. 5가지 진단 기준(Table 1)도 함께 제시하였는데 만성 통증이 지속되거나 재발한 경우 3개월 이상일 것, 통증이 척추 수술 후 시작하거나 재발한 경우, 수술 전보다 더 높은 강도로 통증이 발생하거나 혹은 수술 전과 다른 양상의 통증이 있을 때, 통증이 수술 부위에 해당하는 등에 있거나 하지 방사통일 때, 감염, 악성 질환, 이전부터 존재하던 통증, 어떤 다른 원인으로 설명되지 않는 통증이 그것이다. 이에 본문에서는 척추수술후만성통증으로 명명하기로 한다.

발생률

외국의 보고에서 척추수술후만성통증의 발생률은 척추 유합술 시행 여부와 관계 없이 척추후궁절제술을 시행한 환자 중 10–40%로[1,4,5] 보고된 바 있다. 그러나 이 보고는 약 20년 전 자료이며 집단 특성이 다른 환자군에서 조사하였을 뿐 아니라 평가 방법도 통일되지 않았으므로 참고만 하는 것이 바람직 할 것이다. 최근 연구에서는 전체 인구의 0.02–2%로 보고된 바도 있다[6]. 수술 종류에 따른 발생률 보고도 존재하는데 미세현미경 디스크절제술(microdiscectomy)은 척추수술후만성통증의 발생률이 낮을 것으로 예상되며 단일 코호트 연구에서 전체 환자의 8.4%로 보고되었다[7]. 다른 보고에서는 수술 후 8주 시점의 수술 성공률은 81%이며 이는 추후 2년까지도 지속되었다고 하였다[8]. 그러나 1년 후 같은 저자가 발표한 바에 따르면, 수술 후 단기 성공률은 수술을 시행한 환자군이 보존적인 치료방법을 시행한 환자군에 비해 높으나, 수술 후 2년 시점에 두 그룹 간의 차이가 없다고도 하였다[9].

척추수술후만성통증으로 재수술을 거듭할수록 성공률은 감소하게 된다는 보고는 익히 알려져 있다. Nachemson [10]은 첫 번째 수술 시행 시 50%, 두 번째 수술 시행 시 30%, 세 번째 수술 시행 시 15%, 네 번째 수술 시행 시 5%의 성공률을 보고하였다. 또한, 치료 과정 중에 척추 수술이 좀 더 일찍 논의될수록, 척추수술후만성통증의 환자수는 증가하였다는 보고들도 있었다[11–13].

건강보험공단에서 2016년 발표한 주요 수술 통계연보에 따르면 주요 33개 수술 중, 일반 척추 수술건수는 4위를 기록하였다. 2016년에 대한민국 인구 10만명 당, 323명이 일반 척추 수술을 시행 받았고 이는 2011년과 비교 시 연평균 1.2% 정도 증가하였다. 또한, 총 수술비용이 5,807억원으로 진료비 상위 7개 수술 중 1위를 차지하였다. 현재, 국내 척추수술후요통증후군의 발생률은 정확히 알려진 바 없으나 이와 같은 일반 척추 수술건수를 감안할 때, 적지 않은 환자가 존재함을 짐작해 볼 수 있다. 또한, 척추 수술건수가 증가할 수록 척추수술후만성통증의 발생률은 높아질 것으로 예상할 수 있다. 반면에, 척추 수술의 술기와 장비가 발전하여도 수 십년 전에 비해 척추수술후만성통증의 발생률은 크게 변하지 않았다는 보고도 있는데 결국, 다른 종류의 수술, 각 척추 외과의의 술기, 환자의 소인과 처해있는 임상 상황 등이 이 질환의 발생에 영향을 미친다고 사료된다. 추후 이러한 인자를 포함한 국내 척추수술후만성통증의 발생률에 대한 조사가 필요할 것으로 생각된다.

원인

척추수술후만성통증의 원인은 단 한 가지로 정의하기 어렵다. 각 보고들이 지적하는 원인은 모두 같지 않지만, 통증 발생의 원인은 여러가지 요인이 복합적으로 관여한다는 것에는 일치점을 보인다.

수술 전, 수술 중 인자

수술 전 인자로는 환자에게 소인이 있는 경우와 척추 외과의에게 원인이 있는 경우로 나뉜다. 환자의 소인 중에 가장 주요한 인자로 지적되는 것은 정신사회적(psychosocial) 요소이다[14–17]. 수술 전 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)에서 관찰되는 구조적 이상보다 정신사회학적 인자가 수술 결과를 예측할 수 있는 강력한 인자라는 보고[14]와 우울증, 불안장애, 신체화 장애, 건강염려증 등이 척추 수술의 예후에 나쁜 영향을 끼친다는 것이 내용이다[15–17]. 또한, 정신사회적 요소와 상해로 인한 법적문제에 연루되어 있을 경우에도 마찬가지로 수술 결과에 악영향을 끼친다는 보고도 있다[18]. 그러나 이러한 소인을 가지고 있는 환자가 척추 수술 적응증일 경우, 수술을 시행하지 않을 수 없으므로 환자의 정신사회학적 요인을 파악하고 적절한 술 전 준비를 시행하는 것이 더욱 바람직하며 수술 후 통증 교육, 필요 시 정신건강의학과의 협진 요청 등을 적극적으로 시행해야 한다. 심리학적 설문점수가 낮은 환자에게 조기에 척추 수술을 시행한 것이 더 나은 예후를 보였다는 보고도 있다. 저자들은 조기에 수술을 시행함으로써 장기적인 스트레스와 통증을 차단한 것이 효과적이었다고 분석하였다. 즉, 술 전 환자의 정신사회학적 소인을 정확하게 파악하여 그에 맞는 치료계획을 세우는 것이 가장 중요하다고 할 수 있다[19]. 이는 통증의사에게도 중요한데 척추수술후만성통증을 호소하는 환자에게 술 전 정신사회적 소인이 존재하였는지 파악하는 것이 치료에 도움이 되며, 만성통증으로 인해 역으로 정신과적 질병이 발생할 수 있으므로 면밀히 환자를 관찰하여야 할 것이다.

척추 외과의의 요인으로는 재수술의 횟수가 증가할수록 낮은 성공률을 보이는 것[10]과 더불어 수술적응증의 부적절한 선택[20], 부적절한 수술 술기가 있다[2,21,22]. 부적절한 수술 술기란 척추 신경이 압박된 외측 함요부(lateral recess), 추간공(neural foramen)이 덜 감압된 경우가 가장 흔하다[21]. 부정확한 수술의 빈도는 대략 2.1–2.7%로 보고된다[2]. 통증센터에 척추수술후만성통증 환자가 내원 시 완전하지 않은 수술로 인한 요인이 있는지 확인하는 것도 매우 중요하다. 수술 자체가 완전하게 이루어 지지 않은 상황에서는 여타의 치료 방법이 효과적이지 않을 수 있기 때문이다.

수술 후 인자

North 등[1]은 척추수술후만성통증의 흔한 원인으로는 경추간공협착(25–29%), 디스크성통증(20–22%), 추간판탈출증의 재발(7–12%), 신경병증성통증(10%), 후관절증(3%), 천장관절통(2%)을 보고하였다. 경추간공협착이나 추간판탈출증의 재발은 기존 질환의 악화나 불완전한 수술의 결과 혹은 수술 주변 구조물의 변화가 원인일 수 있다. 수술 위, 아래의 인접 부위(adjacent segment)의 역동성 증가로 척추전위증(spondylolisthesis), 척추협착증 자체가 빠르게 진행되는 경우도 있다[23,24]. 이는 척추의 불안정성으로 이어지기도 한다[25]. 수술 후 인접 부위의 질환은 6–27%의 빈도로 발생하며 재수술로 이어지는 흔한 원인이기도 하다[25–27].

척추수술후만성통증의 원인 중 하나인 경막외유착(epidural fibrosis)은 경막외 공간에서 척추 수술을 시행하게 되면 일어나는 섬유화에서 기인한다. 경막외유착으로 인해 척추 수술 후 통증이 발생하는 빈도는 전체 환자 중 20–36%라는 보고가 있다[2]. 그러나 척추 수술 시 불가피하게 거의 모든 환자에게 섬유화가 일어나는데 이 현상이 반드시 통증과 연결되는지, 환자마다 다른 예후를 보이는 이유에 대한 논란이 지속적으로 있어 왔다[28,29]. 경막외유착 자체가 원인이 되는 것이 아닌, 유착으로 인한 척추 신경의 당김, 허혈, 신경 주변의 영양을 공급해주는 뇌척수액 흐름의 방해가 직, 간접적인 원인이 된다고 볼 수 있다[2].

척추와 골반사이의 불균형, 수술 부위 주변의 근긴장으로 인한 근막통증증후군, 수술 중 출혈 혹은 과도한 신경 견인으로 술 후 하지 방사통의 원인이 되는 Battered root syndrome도 확인이 필요하다[2].

진단

척추수술후만성통증의 진단에 있어 환자의 현 통증이 다른 심각한 원인에 의한 것은 아닌지 확인하여야 하며 이는 치료 계획을 수립하기 위해 필수적이다. 척추수술후만성통증의 원인이 다양한 만큼 통증의 원인을 다각도로 추정해보는 것이 중요하다. 또한, 응급상황인지 아닌지 판단하는 것도 중요한데 자세한 병력 청취와 이학적 검사 및 적절한 영상진단이 도움이 된다.

병력

통증의 특성과 수술 전 통증양상과의 비교

Red flag sign의 확인

수술명과 수술 후의 치료

통증치료 시도 여부와 효과 확인

정신사회학적 소인의 평가

여타 내과적 질환의 존재 유무

Red flag sign이란 생명을 위협할 수 있어 응급을 요하는 징후로써 특별히 요통과 연관된 징후는 Table 2와 같다[20].

영상진단 및 진단을 위한 신경차단술

단순방사선촬영은 척추의 굴곡(flexion)과 신전(extension)을 포함한 전후, 측면영상이 도움이 된다. 수술 위치, 척추의 배열, 척추의 불균형, 불안정성 그리고 퇴행성 변화가 존재하는지 확인할 수 있다. 단순방사선영상의 장점은 척추의 역동적인 상황을 관찰할 수 있다는 것이다[30]. 단점은 연부 조직을 관찰할 수 없으므로 척추협착증 유무 및 정도를 진단하기 어렵고 연부 조직과 관련된 병변은 진단할 수 없다. Computed tomography (CT)의 경우 MRI에 비해 척추의 기구가 삽입되어 있을 때 좀 더 정확하게 주변부를 관찰할 수 있는 장점이 있다. 수술 인접부위의 퇴행성변화, 전방전위증의 악화, 후관절의 퇴행성 변화를 확인하는데 용이하다. 또한, 심박동기 삽입 혹은 뇌동맥류 결찰술을 시행 받은 환자의 경우 MRI를 대체하기도 한다. 컴퓨터단층촬영 척추조영술(CT Myelogram)은 뼈 구조물에 의해 척추 신경이 압박되는 부위를 좀 더 잘 밝혀낼 수 있다. MRI는 연부조직, 감염, 경막외유착 등을 관찰하는 데 유용하다.

척추수술후만성통증 환자에게 후관절, 천장관절, 디스크는 통증의 원인일 수 있어 검사가 필요하며 축성 통증(axial pain)의 원인으로 분류된다. 후관절은 만성 요통의 원인 중 15–40%를 차지하며[2], 반복적인 요추 수술을 받은 환자 16%에서 후관절로 인한 통증이 관찰된다[31]. 그러나 여타의 영상검사가 후관절의 이상을 밝혀 내긴 어렵다고 알려져 있으며 진단을 위한 후관절 차단, 내측지 신경차단이 유용할 수 있다. 또한, 최근 골 단일 광자 단층촬영(bone single photon emission computed tomography)을 이용하여 후관절의 병변을 밝혀 내기 위한 노력이 계속되고 있다[32–34]. 천장관절증은 척추수술후만성통증 환자에게서 약 2%에서 일어난다고 추정된다[35,36]. 병력과 이학적 검사로 진단하기 어려우며 진단을 위한 천장관절차단이 유용할 수 있다[37].

디스크로 인한 척추 수술 후 통증은 이전 두 연구에서 각 17.5%, 21.5%의 빈도로 보고되었다[35,36]. 그러나 영상 검사에서 디스크의 이상이 관찰된다고 해서 임상 증상과 반드시 연결되는 것은 아니라는 이견도 있다. 왜냐하면 통증이 없는 일반 인구에서도 영상검사에서 디스크의 이상이 발견되는 경우가 흔하기 때문이다[38,39]. 그러므로 요추디스크 조영술(lumbar discography)을 통해 통증을 유발시키는 방법이 제안되는데 증상이 없는 경우에도 40%에서 통증이 유발되어 위양성 가능성이 높다[40]. 최근 여러 디스크 조영술에 관한 논문을 분석한 결과, 디스크 조영술 시 유발되는 통증은 전체 환자의 16.9–26%까지 보이며 이 환자들 중 실제 디스크의 파열은 16.9–42%에서 관찰되어 특히, 요추의 디스크 조영술이 진단적 가치를 지닌다고 보고되기도 하였다[41]. 디스크 조영술 이후에 CT 촬영을 실시하여 디스크의 섬유륜 파열 여부를 확인하고 통증의 원인을 찾게 되며 파열 정도에 따라 등급(grade)을 나누게 된다. 1987년 Dallas discogram description으로 제안[42]되어 현재는 Modified Dallas Discogram을 주로 사용한다[43]. 그러나 디스크 조영술과 섬유륜 파열의 확인만으로 디스크성통증(discogenic pain), 디스크내장증(inernal derangement of disc)을 진단하기에는 제한점이 있으며 환자의 임상 증상과 이학적 검사 등을 종합하여 판단해야 할 것이다.

척추수술후만성통증 환자 중 하지 방사통만을 혹은 축성통증과 하지 방사통을 함께 호소하는 경우도 흔하다. 하지 방사통의 원인은 이학적 검사와 MRI를 통해 척추 신경이 압박되는 부위를 확인하는 것이 중요하며 추간공 경막외강 신경차단술(transforaminal epidural nerve block)이 진단 및 치료에 도움을 줄 수 있다. 이는 추궁간(interlaminar) 혹은 미추(caudal) 경막외강 신경차단술에 비해 특정 척추 신경에 집중적으로 국소마취제 및 스테로이드 주입을 시행하여 증상 완화 여부를 통해 진단에 도움을 줄 수 있다[44,45].

치료

척추수술후만성통증의 치료는 다양하며 단일 치료가 아닌 다학제적 치료가 이루어져야 한다는 것은 각 연구가 일치점을 보인다. 또한, 척추 외과의, 통증의사, 재활의학과 및 정신건강의학과 등의 협진이 요구되기도 한다.

보존적 치료(conservative management)

약물치료

제1차 약제로는 비스테로이드성 항염증제(nonsteroidal anti-inflamma춗ory drug, NSAID)가 추천되며 만성요통에 효과를 보인다고 알려져 있으나 하지방사통에는 효과가 없다는 보고도 있다[46,47]. 또한, 뇌졸중, 위장관계출혈, 신부전 등의 합병증을 유발할 수 있어 주의를 요한다. Paracetamol은 요통에 효과가 없다는 보고도[48] 있으나 Tramadol과 함께 사용 시 처방이 권장되기도 한다[49].

마약성 진통제는 tramadol, codeine 등 약한 작용제(weak agonist)의 경우, 통증과 기능을 개선시키며 소염진통제의 원치 않는 부작용을 줄인다고 알려져 있으나 추가적인 연구가 필요하다[50]. 강한 작용제(strong opioid)인 morphine, oxycodone 등은 요구될 경우가 있으나 의존성으로 인해 처방에 주의하여야 한다. 또한, 척추수술후만성통증 환자에게 마약성 진통제의 처방 기간 제한, 약제의 장기 투여 시 위험성에 대해 명확히 알려져 있지 않으므로 처방이 권장되지는 않는다[51].

항우울제와 항전간제는 척추수술후만성통증 환자를 위한 처방권고가 마련되어 있지 않으며 신경병증성 통증에 준하여 처방한다. 2010년에 개정된 European Federation Neurological Society의 신경병증성 통증 가이드 라인에 따르면 삼차신경통을 제외하고 항우울제 중 TCA, 항전간제 중 Gabapentin, Pregabalin을 제1차 약제로 추천한다[52]. 경구약물의 단독 투여로는 증상이 완전히 호전되기는 어려우며 효과가 있는 다른 치료와 병행하는 것이 바람직하다.

중재적 치료(interventional management)

경막외강 스테로이드 주입(epidural steroid injection): 경막외강은 해부학적으로 경, 흉, 요추로 나뉘며 접근법에 따라 후궁간(inerlaminar), 경추간공(transforaminal), 미추(caudal) 경막외강 신경차단으로 분류된다. 경막외강 스테로이드 주입은 염증이 존재하는 압박된 신경 주변에서 일어나 통증과 기능을 개선시킬 수 있는데 주로 요통환자를 대상으로 연구가 이루어져왔다. Abdi 등[53]에 따르면 경추 부위의 후궁간 경막외강 스테로이드 주입은 장기간의 통증 감소를 가져오나 요추에서는 근거가 부족하며 경추간공 접근법의 경우 두 부위 모두에서 중등도(moderate) 이상의 근거를 가진다. 또 다른 연구들은 경추간공 접근법이 하지방사통에 효과가 있으며 강한(strong) 의학적 근거를 가진다고 주장하였다[54,55]. 그러나 위 연구들은 척추수술후만성통증 환자에게만 이루어진 것이 아니며 수술 후 해부학적 변화, 기구가 삽입된 상태, 경막외강유착으로 인해 환자에 따라서는 각 시술이 용이하지 않을 수 있다는 단점이 있다. Manchikanti 등[56]은 척추 수술 후 6개월 이상의 요추 및, 혹은 하지 방사통을 호소하는 환자들에게 미추 경막외강 신경차단시, 60–70% 환자가 스테로이드 여부에 관계없이 효과를 보인다고 하였다. 그러나 후관절이 원인이 될 경우 미추 경막외강 신경차단은 효과가 없었다. 경막외강 스테로이드 주입은 환자의 증상에 따라 적절한 접근법을 선택하여 척추수술후만성통증의 진단 및 치료 계획 수립을 위해 시행해볼 수 있겠다.

후관절 차단술(facet joint block), 내측지 신경차단술(medial branch block) 및 고주파 열응고술(radiofrequency thermo춃oagulation): 척추수술후만성통증 환자가 축성통증을 주로 호소하거나 경막외강 신경차단에 반응이 없을 경우 후관절에 통증의 원인이 있다고 의심해야 한다. 이 경우 후관절 신경차단이나 내측지 신경차단술이 진단 및 치료에 도움을 줄 수 있다. 진단적 차단술을 통해 후관절성 통증이 진단되면 내측지 신경의 고주파 열응고술을 시도해볼 수 있다. 요통환자를 대상으로 내측지 신경차단에 통증감소가 관찰되어 고주파 열응고술을 시행할 경우, 83%의 환자에게 10.5개월 이상의 통증 감소를 보였다[57]. 이전 척추 수술의 과거력이 있는 환자들을 대상으로 같은 연구를 시행 시 이전 수술력이 결과에 영향을 미치지 않았다[58].

천장관절증이 통증의 원인일 경우 천장관절차단을 시행하여 진단 및 치료를 시행하고 장기적인 효과를 위해 고주파 열응고술 혹은 고주파 냉각술이 시도된다. 천장관절은 여러 개의 신경분지에 의해 지배를 받고 제4, 5 요추의 후지, 제1–3 천추의 외측지가 고주파의 목표 구조물이다[59]. 최근 리뷰 논문에서 천장관절 내 스테로이드 주사, 고주파 열응고술보다 고주파 냉각술의 의학적 근거가 더 높다고 하였으나[60] 추가적인 연구가 필요하다.

경피적 경막외강 유착용해술(percutaneous epidural adhesiolysis, PEA): 경막외유착(epidural fibrosis)은 경막외 공간에서 척추 수술을 시행하게 되면 일어나는 섬유화이다. 거의 모든 환자에게 발생하는 경막외유착이 통증의 원인 인지에 대하여 오랜 기간 이견이 있어 왔다. MRI에서 관찰되는 경막외유착의 범위가 넓을수록 수술 후 통증이 심하였다는 보고가 있는데 이는 경막외유착 자체가 통증의 원인이 아니라 경막외유착으로 인한 주변 조직의 허혈 및 만성 염증이 원인이라고 지적할 수 있다. 120명의 척추수술후만성통증 환자에게 미추 경막외 신경차단과 PEA의 결과를 비교하였을 때 PEA를 시행 받은 환자의 73%가 1년간 통증과 기능의 개선을 보였다[61]. 그 이후 연구에서 단기간 혹은 장기간 통증과 기능의 개선을 보였고[62,63] 기존의 경막외강 신경차단에 비해 우월한 효과가 있음을 보고하기도 하였다[64,65]. PEA는 여타 보존적 치료 방법에 불응할 경우, 특히 하지방사통이 주요 증상일 때 시도해 볼 수 있다고 생각된다.

내시경적 경막외강 유착 용해술(endoscopic epidural adhe춖iolysis, EEA): EEA는 PEA에 비해 경막외강 내를 직접 눈으로 관찰하며 치료할 수 있다는 장점이 있다. 경막외강 신경차단이나 PEA에 치료효과가 미미할 경우 시행한 내시경에서 유착 용해술을 시행한 그룹과 아닌 그룹을 비교 시, 시행한 환자의 57%가 6개월 시점까지 유의한 통증 감소를 보였다[66]고 하였는데 같은 저자가 보고한 후향적 논문에서는 PEA가 통증감소와 비용효과면에서 더 우월하다고 하여 이견이 있다[67]. 또한, 경막외강 신경차단과 EEA를 비교 시 통증 감소면에서 큰 차이를 보이지 않았다는 결과도 존재한다[68]. EEA는 더 많은 척추수술후만성통증 환자를 대상으로 추가적인 전향적 연구가 필요하다고 생각된다.

Intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET), Nucleoplasty: 척추수술후만성통증의 원인이 디스크 조영술과 CT를 통해 디스크의 섬유륜 파열로 확인 될 경우 디스크 내 감압을 위해 IDET 혹은 Nucleoplasty가 시행될 수 있다. 이 시술들은 디스크성 통증을 장기간 효과적으로 낮추며 하지방사통이 동반된 경우에도 효과적이라는 보고[69,70]가 있는 반면, 다른 보존적 치료와 비교 시 큰 차이가 없었다는 보고도 있어 이견이 있다[71].

척수자극기(spinal cord stimulator)와 척수강 내 약물주입 펌프(intrathecal drug delivery system)

척수자극기 삽입은 척추수술후만성통증 환자의 치료 방법 중 하나로 제안된다. Kumar 등[72]은 디스크 제거 수술 이후에도 하지방사통을 호소하는 100명의 환자를 약물치료만 하는 군과 척수자극기 삽입을 병행한 군으로 나누어 관찰하였을 때 12개월 시점에서 병행군이 통증과 기능의 감소를 보이는 것을 확인하였다. 2년 뒤, 병행군의 환자 42명을 추적 시 효과가 지속되는 것을 확인하였으나 45% 환자에게서 척수자극기 삽입관련 부작용이 발견되어 이를 교정할 필요가 있다고 주장하였다[73]. 비용 효과를 조사한 연구에서 척수자극기 삽입이 더 우수함을 증명하기도 하였다[74,75]. 척수자극기는 척추수술후만성통증 환자 중 난치성 하지 방사통을 호소하는 경우 적용해 볼 수 있지만, 기존의 보존적 치료에 효과가 없는 경우 고려해야 할 것이며 삽입 이후 합병증과 관리의 문제가 존재하므로 시술을 결정시 신중하게 고려해야 한다.

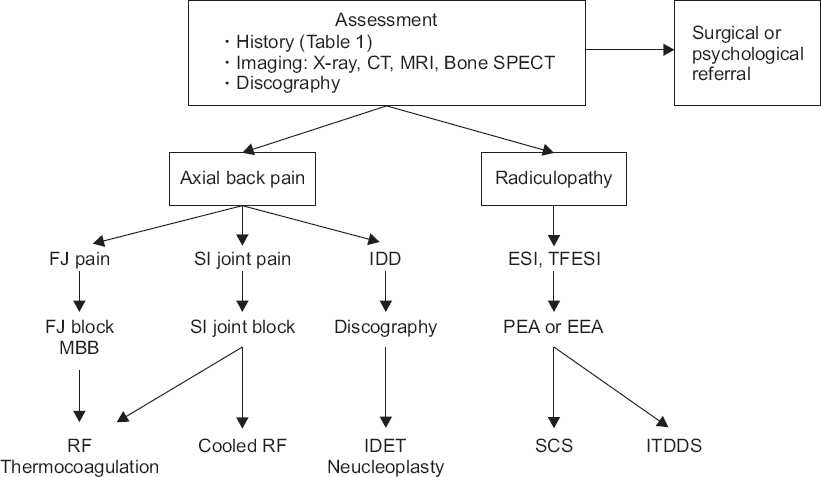

척추수술후만성통증 환자에게 적용된 척수강 내 약물주입 펌프의 효과는 아직 정립되지 않았다. Hamza 등[76]의 연구에서 전체 58명의 환자 중, 35명이 척추 수술 후 통증환자, 그 외 요통, 복합부위통증증후군, 복통, 골반통 환자에게 척수강 내 약물펌프 삽입을 적용하였다. 3년 추적 관찰 시 전체 70%의 환자가 50% 이상의 통증 개선, 30%의 환자가 기능개선을 보였다[76]. 척수강 내 약물 펌프의 경우 경구용 마약성 진통제를 과량 복용할 경우, 이를 척수강 내 주입으로 전환함으로써 소량의 마약성 진통제로도 통증을 조절이 가능하다. 91명의 비암성 통증 환자에게 펌프 삽입 이후 마약성 진통제를 효과적으로 중단할 수 있었다는 보고도 있다[77]. 그러나 척추수술후만성통증 환자에게 전향적, 장기 추적 관찰 연구가 부족한 점, 국내에서 사용할 수 있는 펌프 삽입약제가 제한적인 점, 기계와 연관된 합병증 가능성 등으로 신중하게 고려하여야 할 것이다. 또한 척수자극기와 효과를 비교한 연구가 아직 없고 두 치료 방법의 원리가 다르므로 각 환자의 상황에 맞춘 선택이 요구된다. 2018년도부터 국내에서는 척수강 내 약물 펌프의 전체 급여화가 실시되어 그 사용이 증가할 것으로 예상된다. 이에 보다 활발한 연구가 뒷받침되어 할 것이다. Fig. 1에서는 통증센터에 환자가 내원 시, 진단과 치료의 알고리즘을 간단하게 도식화하였다.

Proposed algorithm for chronic pain after spinal surgery. CT: computed tomography, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, SPECT: single photon emission computed tomography, FJ: facet joint, SI: sacroiliac joint, IDD: internal derangement of disc, ESI: epidural steroid injection, TFESI: transforaminal epidural steroid injection, MBB: medial branch block, PEA: percutaneous epidural adhesiolysis, EEA: endoscopic epidural adhesiolysis, RF: radiofrequency, IDET: intradiscal electrothermal treatment, SCS: spinal cord stimulator, ITDDS: intrathecal drug delivery system.

결론

척추수술후만성통증은 척추 수술이 시행되는 한, 지속적으로 발생할 수 밖에 없다. 발생 시 재수술을 결정하는 경우는 드물고 수술의 횟수가 거듭될 수록 수술 성공률이 낮아지므로 비수술적 요법으로 환자의 증상을 조절하려는 경향이 두드러진다. 이에 통증센터에서는 환자의 수술 전 상황부터 시작하여 통증의 원인을 면밀히 찾아낸 후, 이에 맞는 영상 진단과 진단을 위한 신경차단 등을 적극적으로 시행해야 한다. 또한, 적합한 비수술적 치료를 시행하여 통증을 완치하거나 감소시켜 삶의 질을 향상시키는데 초점을 두어야 한다.