The efficacy of vitamin C on postlaparoscopic shoulder pain: a double-blind randomized controlled trial

Article information

Abstract

Background:

This study evaluated the effect of vitamin C on post-laparoscopic shoulder pain (PLSP) in patients undergoing benign gynecological surgery during the first 72 h.

Methods:

Sixty patients (aged 20 to 60 years, with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification I or II) scheduled for elective laparoscopic hysterectomy were enrolled in this study. The vitamin C group (Group C) received 500 mg of vitamin C in 50 ml of isotonic saline infusion intravenously twice a day from the day of surgery to the third day after surgery. Patients in the saline group (Group S) received the same volume of isotonic saline over the same period. Post-operative analgesic consumption, pain scores of the incision site and the shoulder, and the incidence of PLSP were all evaluated at 1, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h following surgery.

Results:

Cumulative post-operative fentanyl consumption was significantly less in Group C at 24 and 48 h after surgery (P = 0.002, P = 0.012, respectively). The pain intensity of PLSP was also significantly lower in Group C 24 h after the operation (P = 0.002). Additionally, the incidence of PLSP was significantly lower in Group C 24 and 48 h after the operation (P = 0.002, P = 0.035, respectively).

Conclusions:

Perioperative intravenous administration of vitamin C (500 mg, twice a day) reduced post-operative analgesic consumption and significantly lowered the pain intensity and incidence of PLSP.

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic surgery has many advantages including a smaller incision size, less post-operative pain, early recovery and a shorter hospital length of stay. These advantages make laparoscopic surgery popular. However, up to 80% of patients complain of shoulder pain after laparoscopic surgery [1,2]. In some cases, patients experience more discomfort from the shoulder pain than pain from the incisional site. It is believed that irritation of the diaphragm by residual carbon dioxide gas is responsible for the pain. Several studies have shown that the volume of residual pneumoperitoneum is positively correlated with shoulder pain [3].

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is a well-known water-soluble vitamin as well as an antioxidant. Furthermore, vitamin C also has neuromodulating and neuroprotective properties [4–7]. In addition, various studies have shown that vitamin C may play a role in chronic pain and post-operative pain management without significant side effects [8–12].

To our knowledge, vitamin C has not been used for PLSP or regularly after operations. Hence, we conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial to examine the effect of vitamin C on PLSP in patients undergoing benign gynecological surgery during the first 72 h post-operatively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty patients aged 20 to 60 years, with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification I or II and who were scheduled for elective laparoscopic hysterectomy were enrolled in the study. Exclusion criteria included patients with cardiovascular disease, neuromuscular disease, renal disease, hepatic disease, cancer, and diabetes. Any patients with cervical cancer or ovarian cancer were excluded. Patients with a history of any allergic reaction to vitamin C, opioid or analgesic abuse, more than 1 month use of vitamin C, chronic shoulder pain, chronic epigastric pain, previous shoulder or upper abdominal surgery, and shoulder or upper abdominal injury were also excluded. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and all patients were given written information. Informed consent was obtained before the operation. The day before surgery, all enrolled patients were taught how to use the patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) system (AutoMed® 3400, Ace Medical, Korea). Patients were randomly assigned to one of the two groups according to the sealed envelope system.

The vitamin C group (Group C, n = 30) received 500 mg of vitamin C in 50 ml isotonic saline infusion intravenously over 10 min twice a day. They received vitamin C at 7 A.M. and 7 P.M. from the day of surgery to the third day after surgery. The saline group (Group S, n = 30) received the same volume of isotonic saline over the same period. The infusion was prepared by personnel at the pharmacy and administered by the nurse (or anesthesiologist) who was blinded to the patient’s group assignment. The data were subsequently collected and analyzed by an anesthesiologist who was also blinded to the study groups. All patients were premedicated with 0.2 mg glycopyrrolate intramuscularly 30 min prior to the surgery. They were monitored using electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, an esophageal temperature probe, ETCO2, and bispectral index (BIS™, Covidient Ltd., Ireland). A peripheral nerve stimulator (TOF Watch SX®, Organon Ltd., Ireland) was also placed at the wrist for monitoring of the neuromuscular block. General anesthesia was induced with propofol (2 mg/kg) and lidocaine (1 mg/kg). Tracheal intubation was facilitated with rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) and the neuromuscular block was monitored throughout the operation. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (1.5–2.5 vol%) in a mixture of oxygen with air (50%), and remifentanil (0.05–0.1 µg/kg/min) to maintain a BIS of 40–60 and an appropriate hemodynamic response. Before inserting the trocars, local anesthetics were not infiltrated. Multiport laparoscopy was used, and the same evacuation process of CO2 was performed at the end of laparoscopic surgery in all cases. Infusion of the anesthetic agent was discontinued at the time of skin closure and all patients received 20 µg of fentanyl, 30 mg of ketorolac and 0.3 mg of ramosetron intravenously. At the end of surgery, pyridostigmine 0.25 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg were used to antagonize the neuromuscular block. After the operation, a PCA device was connected to the intravenous line and the patients were transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). The PCA solution contained 10 µg/ml of fentanyl in isotonic saline, and the device was programmed to administer 1 ml of a bolus dose, with a 5 min lockout interval and no basal infusion. An anesthesiologist who was blinded to the study group then evaluated pain, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and total PCA analgesic solution consumption. Vital signs were checked every 20 min during their stay in the PACU and at 6, 24, and 48 h after discharge from the PACU. Pain scores were evaluated using the verbal numerical rating scale (NRS) where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst pain ever. The day after surgery, pain scores were evaluated at rest time and during movement. Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) were recorded both by the incidence and the number of vomiting episodes.

The primary outcome measured was the incidence of PLSP. A pilot study showed that the incidence of PLSP within 24 h after operation was 67% (6/9). Our target was an incidence of 30% PLSP, hence a minimum sample size of 28 patients were required per group providing an alpha value of 0.05 and a beta value of 0.2.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., USA). Continuous data were reported as mean ± standard deviation and other data (American Society of Anesthesiologists, NRS, and PONV incidence) were reported as counts or percentages. Differences in American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status and the incidence of PLSP and PONV were analyzed using chi-square test. Whenever the expected values in each cell of a contingency table were below 5, Fisher’s exact test was used. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare measurements of post-operative pain scores (NRS) from the incision site, shoulder, as well as the total amount of fentanyl required. For repeated measures ANOVA, the sphericity assumption was evaluated with Mauchly’s test, and based on those results, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was performed. If there was a statistical difference (P < 0.05) in repeated measures ANOVA, Student’s test for post-hoc analysis was then used to compare the data at each time point. In student’s test (post-hoc analysis), P values below 0.0167 (0.05/3, corrected by Bonferroni’s method) were considered statistically significant at each time point.

RESULTS

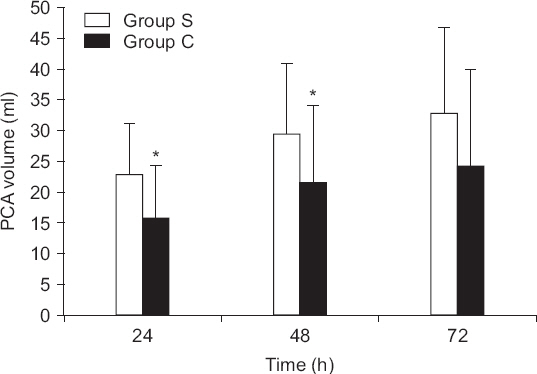

There were no significant intergroup differences in age, height, weight, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, operation time, anesthetic time, and duration of hospital stay (Table 1). The incidence of PLSP (Group S and Group C, respectively) were 66.7% and 26.7% at 24 h, 53.3% and 26.7% at 48 h, and 33.3% and 20.0% at 72 h. The incidence of PLSP showed statistically significant differences at both 24 and 48 h after the operation (P = 0.002 and 0.035, respectively) (Table 2). There was also a significant difference between the two groups in cumulative post-operative fentanyl consumption (P = 0.008). The cumulative post-operative fentanyl consumption was significantly less in Group C than Group S at 24 and 48 h after operation (P = 0.002 and 0.012, respectively) (Fig. 1). The NRS score of PLSP showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001), especially at 24 h following surgery (P = 0.002) (Table 3). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to the post-operative incision site pain scores (P = 0.659 at rest and 0.171 during walking, respectively) (Table 4). There were also no significant intergroup differences in the incidence of PONV at each time point (Table 5).

Cumulative fentanyl consumption. Mean cumulative injected volume of the intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA) solution in the four groups. The error bars show standard deviation. Group S: saline group, Group C: vitamin C group. *Indicates significant difference between saline group and vitamin C group.

DISCUSSION

This placebo controlled, double-blind study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of vitamin C on PLSP in benign gynecologic surgeries. Our study showed that perioperative administration of vitamin C reduced the incidence of PLSP, the NRS score of PLSP, and total post-operative analgesic consumption. There was no significant difference in the NRS score of the incision site pain and the incidence of PONV between the two groups.

Due to its numerous advantages, laparoscopic surgery has become a popular alternative method to open surgery. However, there remains a relatively high incidence (up to 80%) of PLSP which results in large amounts of patient discomfort during the first 24 to 72 h following surgery [1,13,14]. It is not uncommon for patients to complain that their PLSP is more severe than the incision site pain and that the PLSP is not improved by conventional analgesic agents such as opioids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [15,16]. Several studies have reported that this pain has a positive correlation with the residual carbon dioxide volume post-laparoscopy as the residual carbon dioxide can irritate the phrenic nerve and peritoneum [17,18]. The phrenic nerve originates from the third to fifth cervical nerves, with shoulder innervation via the fifth to sixth cervical nerves. This common innervation might explain the correlation of PLSP with residual carbon dioxide. Sarli et al. [18] showed that low pressure carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum reduced both the frequency and intensity of PLSP following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Nutthachote et al. [19] showed that perioperative administration of pregabalin reduced PLSP and the amount of analgesic consumption in patients undergoing elective laparoscopic gynecologic surgery. Finally, Tsai et al. [20] showed that a combined approach with pulmonary recruitment maneuvers and intraperitoneal normal saline infusion reduced PLSP. To date, several clinical studies have investigated methods for reducing PLSP, but there have been no cases of perioperative vitamin C use for PLSP in the literature.

The exact anti-nociceptive mechanism of vitamin C and its site of action are not well understood. Several properties of vitamin C may play a role in its analgesic effect. Oxidative stress is associated with arthritis, CRPS, infection, cancer, and surgical trauma [5]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediate neuropathic pain, and scavenging ROS has been shown to relieve mechanical discomfort in a rat model [21]. These properties of vitamin C, in particular its anti-oxidative effects and the role of ROS scavengers probably contribute towards pain relief. Furthermore, vitamin C acts as a neuromodulator in dopamine and glutamate mediated neurotransmission [6]. Through the redox changes on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor by vitamin C, pain is decreased in chemical behavioral models of nociception in mice [22]. These analgesic functions of vitamin C exhibit a different mechanism from the conventional analgesics such as opioids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Moreover, within 24 h of acute injury, the plasma concentration of vitamin C decreases below normal levels and the vitamin C requirement is increased in surgical patients [23]. Although the detailed mechanism of vitamin C for nociceptive pain is not yet known, several studies have shown that vitamin C is a useful adjuvant for post-operative acute pain management. Through these studies, we hypothesized that vitamin C may be effective for shoulder pain. Kanazi et al. [12] showed that supplementation of vitamin C before surgery decreased post-operative morphine consumption in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Jeon et al. [10] showed that a perioperative infusion of vitamin C decreased post-operative pain scores during the first 24 h and reduced morphine consumption in patients undergoing laparoscopic colectomy. Although numerous authors have reported on the clinical efficacy of perioperative vitamin C infusions, this is the first study to examine the use of vitamin C for PLSP in patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy.

From the pilot study we recognized that PLSP began in most of the patients approximately one day after surgery, with a peak in the incidence and intensity during the first three days, after which it slowly subsides. Other clinical studies showed both a similar disease course and characteristics. Lee et al. [2] showed that PLSP reached a peak about 24 h after surgery, did not last for more than a week, and gradually subsided. Thus, we used vitamin C for 3 days from the day of surgery in the present study.

We decided to administer 500 mg of vitamin C intravenously twice a day because vitamin C has a low absorption rate through oral intake and a short half-life in plasma. Oral absorption of vitamin C is approximately 63% at 500 mg and 46% at 1,250 mg. Steady state plasma vitamin C concentrations rarely exceed 80 µmol/L due to rapid renal clearance [18]. In addition, gastrointestinal problems such as osmotic diarrhea were reported in oral intake of vitamin C over 5 g [24,25].

In the present study, the incidence of PLSP and post-operative fentanyl consumption decreased at the same point (24, 48 h). This might be due to the natural course of PLSP. PLSP peaks approximately 24 h after surgery which could then increase the consumption of analgesics. Due to the gradual decrease of PLSP, there were no significant differences in the incidence of PLSP and post-operative fentanyl consumption at 72 h after the operation.

The present study had a few limitations. First, although patients who took vitamin C for a long time were excluded in advance, we did not evaluate the plasma concentration of vitamin C in the two groups. Vitamin C has a short half-life, but further evaluation regarding the plasma concentration of vitamin C may be needed. Second, we only focused on patients undergoing the same type of surgery (laparoscopic hysterectomy) in the present study. It is possible that different types of surgery might influence the outcome. Third, we did not utilize any manual therapy or intervention which are known to be effective for PLSP [20,26]. As different clinicians or hospitals may use varying methods, additional experiments are needed. Finally, the ideal amount of vitamin C has not yet been determined.

Post-operative pain management is very important for both patients and clinicians [27]. Opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs still play a major role in post-operative pain management. A multimodal approach to pain management improves the outcome of surgery, the perioperative recovery process, and lessens the dependence on any given medication [28]. Numerous clinical studies have shown that vitamin C could be an adjuvant analgesic for perioperative pain management as it is relatively safe to use. In the present study, there were no side effects caused by vitamin C injections.

In conclusion, this study reports on the effect of perioperative vitamin C on PLSP following laparoscopic hysterectomy. Pre- and post-operative administration of vitamin C (500 mg intravenous infusion by twice a day) significantly reduced analgesic consumption following surgery. A reduction in the incidence and scores of PLSP was also found.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

ORCID

Sungho Moon: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3602-9441

Kwangrae Cho: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9805-9582

Myoung-hun Kim: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4350-0078

Wonjin Lee: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6240-7370

Yong Hyun Cho: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1334-3531